Dear Admin, It’s Time to Address the Dress Code

Is showing your shoulder a crime? After a year of online school, we all have questions about the explosion of rules we were acquainted with at the beginning of the year. While it differs in each division, the most common and easily enforced rule is the dress code. For 10-12, the dress code is the most relaxed with the allowance of ripped jeans, hats, and tank tops. Essentially, you just have to be covered from your armpits to 2 inches of your legs with straps or sleeves. For 8-9, the dress code includes the coverage of shoulders to mid-thigh, including undergarments. Despite the extent of the dress code, we all know that it is by far the most controversial rule at Albuquerque Academy. As Alyssa Portnoy ‘23 put, “It’s offensive, [and] it continues a stigma. Not only does it pretty much only apply to girls, but it’s ridiculous.”

The current 10-12 dress code was established a few years ago after a semester-long experiment of students working with Dr. Lenhart, the 10-12 division head. As a former Academy student, Dr. Lenhart’s own experiences led her to “feel very strongly that students’ voices had to [collaborate] together in building the dress code.” That’s why, in comparison to other schools or even other divisions, the 10-12 dress code especially tries to avoid language rooted in sexism or racism. Despite these changes, many students believe that we still face the unintended consequences of the dress code.

The root of the dress code’s problems stems from its purpose. Mr. Anderson, a 10-12 dean, struggles most with this question as he explains that, “fundamentally we are trying to establish a policy that promotes an institution of learning where a level of professionalism is expected.” Similarly, Mrs. Short, a dean in 8-9, further explains that the dress code is to “present almost a workplace-like atmosphere in a sense that we’re here to learn first and foremost.” There is, however, a large disconnect between the intended purpose of the dress code and its effects in practice. After becoming a national champion in speech and debate for giving an originally written speech about the dress code, Addison Fulton ‘22 explains that “A lot of the time, the dress codes’ purpose is, unintentionally, a relic from a time where women’s bodies were considered so dangerous to societal health as a whole that they had to be controlled. So the unintended purpose [of the dress code] is to keep a lid on specifically women and other marginalized groups’ self-expression, even if that’s not what the people who originally created the dress code think that’s what the dress code is.” So, while unintentional, the very idea of a dress code is limiting womens’ self-expression and participation in the workplace.

The controversy behind the dress code begins with its origins. The purpose of this rule, professionalism, originates from the ancient idea of what constitutes the professional class. From the very beginning, this definition was limited to aristocratic white men, representing an exclusive, patriarchal, and racist society that continues to inform the basis of today’s rules. With a progressive shift in society, how do we create a standard of professionalism for everyone else? In 1973, the blatantly sexist answer was given in the Idaho Supreme Court’s decision to actively prohibit women’s right to wear pants: “The wearing of… slacks or pantsuits by female students results in a detrimental effect on the morals of the students attending the school and upon the educational process; …wearing slacks and pantsuits results in unsafe conditions and safety hazards at the school [and] leads to… an increased amount of physical contact and familiarity between boys and girls in school surroundings.” In practice, this ruling creates a legal precedent for victim-blaming. Female-presenting students are told that their clothing is to blame for “unsafe and hazardous conditions” involving men. Fortunately, from shocking ankle socks, high neck collars, to scandalous pantsuits, our allowance of self-expression has increasingly become less sexist. While these rules may seem archaic now, they were justified with the same standard of professionalism as the current dress code. Rather than encouraging a productive work environment, this definition of professionalism measures women’s clothing to the standard of male comfort. This fundamental, but tacit, understanding of professionalism has shaped women’s participation in the workplace. Dr. Michael Anne Sullivan, a 10-12 history and humanities teacher equates this phenomenon to “breaking into the club.” “As more and more women enter the workplace, they adopt masculine standards of dress to be taken seriously to break into the club,” she explains. The foundational purpose of our school’s dress code shapes the way our female-presenting students see themselves not only at school but also in their future professional spaces. The dress code teaches people who identify as female at a young age that their success depends on their ability to conform to male standards.

So, how do these dangerous implications impact our own school environment? An anonymous male junior’s worst experience with the dress code was “In eighth grade [when] I wore ripped jeans and one teacher said ‘you need to get those taped up’ and then I didn’t get them taped up.” However, in another experience with a teacher, Zoe Beck ‘23 says she was told: “[she] looked like [she] was going clubbing during…class.” Personally, a teacher has also approached me while getting my shoe tied by asking me, “How would your mother feel with you dancing around like that in such short shorts?” God forbid I tie my shoes in the presence of males. Adam Blanchard, another male junior’s, worst experience with the dress code is, “Honestly being told to take off my hat or a hood. [I’ve] never actually been truly dress coded, just not to wear a hat because that’s pretty much the only rule that applies to men’s fashion. Not even a serious talk, just told to take off my hat.” Even Mr. Anderson admitted that 100% of the people he dress-codes for clothing are female. The dress code systematically targets female-presenting people, compromising their comfort and participation in educational environments.

If anything, the dress code prevents Mrs. Short’s idea of learning first and foremost. Those who identify as female are disproportionately “distracted” from their work environment when middle-aged teachers, who we are supposed to trust, make comments rooted in the sexualization of our bodies. How would their children feel about them commenting on the clothing of minors? Given its history, the dress code not only makes women uncomfortable in our own academic environments but also quite literally limits our participation. While we have all broken the dress code, the anonymous junior and Adam have never faced academic repercussions, whereas Zoe, me, Bella Tolk ‘24 who was, “taken out of class” and Anodyne Smith ‘24 who was, “stopped in the hallway and made 10 minutes late to class to talk about the dress code” have felt the dress code’s effect on our academic careers. Female-presenting students are not only specifically targeted by the dress code and its interruptions in our academic lives, but we are also addressed in a much different manner when out of the dress code. I highly doubt that a teacher would use a mother’s opinion to shame a male. This is why Addison’s speech was specifically written to point out that “women’s issues with dress codes are not just ‘but I want to wear a crop top.’ They’re indicative of a really deep societal issue with how we treat women in academic and professional spaces.” The message our institution projects through the dress code upholds a culture of over-sexualization and victim-blaming. In the words of Madison Konker ‘24, “If you…can’t control yourself…then there’s something wrong with you, not my body.”

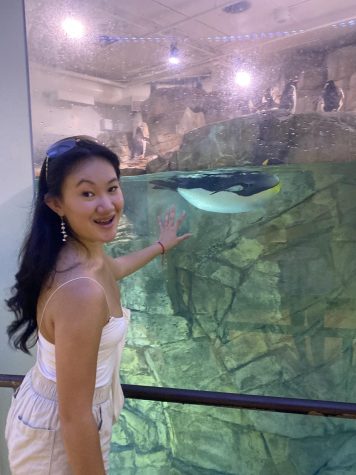

Writing for the Advocate since junior year, and now the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Coordinator, Sophia is drawn to articles that she is passionate...

Zeriah • Oct 25, 2022 at 8:24 pm

I’m so very tired of this dress code like why do we even need it also I’m in middle school and the other day I just got dress coded because of a male teacher who is a pervert and all the girls know it but not only that it was a small rip on my mid thigh and I got sent to the principals office just because of it and I am sick and tired of this damn dress code!

Rebecca • Nov 19, 2021 at 11:49 pm

As an AA alumna, I am absolutely astonished at the level of sexism and outright harassment you are reporting. This sounds like a scene from the 1960s but your class years are in the 2020s. What Zoe has related seems particularly legally actionable but given your identification of a pattern of disruption to your learning as a female-identifying student, I should think you all have a case to bring against the institution for harassment/discrimination. At a public institution this would be a Title IX violation no-brainer (I happen to teach at such an institution where what you have reported would get faculty reprimanded and even dismissed). What especially concerns me is what this policing of and control over female bodies is modeling for young male-identifying students. I was bullied and harassed relentlessly by male-identifying students as a female student there in the 1990s and I hate to see AA continue to embrace a culture that cultivates harassment and, via these behaviors, assault, through both the sanctioned policing of female bodies and the turning of a blind eye to *harassment* which is what the instances you’ve described are. Again, I’m totally disgusted and I commend your excellent, brave reporting.

Jonah Gutow • Nov 14, 2021 at 1:56 pm

I am biologically male, but that does not stop me from identifying with this article. All my life I have been raised not to tolerate discrimination/any of the “isms”. I’ve had friends get dress coded for things that aren’t even against the code, or for something out of their control. I’ve even heard horror stories and rumors about teachers calling students sexist slurs. Teachers. Calling students slurs. That is so messed up. School is supposed to be a safe learning environment, they say it themselves. This outdated dress code and system built off of implicit biases has to change and it has to change soon.

Thanks for reading my rant, sorry it was so long.

Lily • Nov 13, 2021 at 9:50 am

This is really well written! I went to Prep so I never personally dealt with this, but I have a lot of friends who transferred from Academy and complained about this a lot. Thanks for saying something, I wish you luck in getting this changed.

AB • Nov 12, 2021 at 7:08 pm

I’ll always remember when I was a freshman in 2017 I was made to call my mom at work to bring me a new pair of shorts to wear to class. Not only disrupting me and my learning, but also disrupting my mom’s work schedule. Never felt so uncomfortable knowing that even being as young as a freshman in high school, older men and women who were my teachers were looking at my body and judging me by the clothes I wore to school.

Mia • Nov 12, 2021 at 3:42 pm

This is really well written, Sophia. Thank you for articulating this issue in a professional manner.

Biff • Nov 12, 2021 at 2:44 pm

Bruv

Natalie Perkins • Nov 12, 2021 at 2:43 pm

Thank you Sophia, this is an incredibly well written article and touched on ideas and opinions that I believe almost all AFAB and female presenting students hold. Thank you for speaking on this, it was long overdue. Almost every day I hear a conversation happening in disapproval of the dress code and I’m glad you took the time to work on this and say basically what everyone else was thinking – that the dress code is not working, and it is wrong. Your takes on professionalism captured it perfectly, and I don’t believe we should hold professionalism as a standard for the dress code when in contradiction, it allows for clothing that is casual and not necessarily “formal” or what is standard as professional which is GOOD. We have a freedom to expression in our dress code, which has no place for unfair standards of professionalism which inherently contradicts itself. The dress code has proven time and time again to not actually have a purpose, as it doesn’t fulfill the standard of professionalism, but rather is in place for the policing and sexualization of people’s bodies. People – who I may add – are a vast majority under the age of 18 and should NOT be sexualized by adults. The numerous passive aggressive comments I’ve heard from deans, the circling in the quad, searching for people to dress code, and the odd stares and behavior from deans and dress code enforcers (predominantly male teachers and deans) have all made students extremely uncomfortable.

Again, amazing article, and thank you for formally bringing this to light.

Dean A Jacoby • Nov 12, 2021 at 2:24 pm

I think Ms. Liem has crafted an outstanding piece of reporting. The effort to hear from male presenting and female presenting students alongside administrators and even the Supreme Court make this a fascinating piece to read.

There are two areas where I would have liked to hear more. First, I would have been interested to hear more from students who are non-binary and their experience with the dress code. Second, as a former Dean of Students, I feel sensitive to this subject. It is easy to criticize as Ms. Liem does very effectively. I missed the part where she clearly stated her recommendation for what the school should do.

Sophia Liem • Nov 12, 2021 at 9:16 pm

Thank you Mr. Jacoby. I completely agree with you. This article would have been benefitted with the inclusion of non-binary voices, and I wish I had incorporated that. As for my recommendation, I apologize that it wasn’t included in the article, but my intention while writing it was to draw attention towards our schools problematic justification for a problematic practice. Also, if criticizing the dress code is easy in your own opinion as a former dean, then I think that alone is indicative of a need for change. That’s why I made it clear that the very message and justification of the dress code is the problem because of its roots. Therefore, my recommendation, as eluded in my last sentence, is that we shouldn’t even have a dress code if it’s projecting a problematic definition of professionality 🙂

Dean A Jacoby • Nov 16, 2021 at 11:34 am

Ms. Liem,

Thank you for your response. I appreciate your further explanation.

I think you make a very strong case for the removal of the dress code. I also think it is clear that you have tapped into a strong current of support and thinking among other students and have expressed their concerns very eloquently. I would like to clarify that my reference to it being easy to criticize was made as a more general reference to the fact that building something is much harder than tearing something down. That does not mean that I stand in uniform (pun intended) support of the dress code.

I wonder if there is a more modern way that we can discuss what one wears without it being a dress code? Is it okay to come to school with a shirt that says whatever the wearer wants without worrying about the impact on others? Is it okay to wear clothes that are created through animal cruelty or signal a level of income that is not shared by all members of the community? Is it okay to come naked (a student at Cal Berkeley famously did this)?

I think an intentional community can discuss these things and find a way to set some standards and expectations.

Sophia L. • Nov 16, 2021 at 8:24 pm

Mr. Jacoby,

I agree with you. I think a more modern conversation is definitely possible, and I actually strongly agree that we should be encouraging a policy that prevents harmful messages from making students feel unsafe, especially given the addition of masks to the dress code. My opinion was never to terminate every facet of the dress code. My issue with the dress code is its justification and encouragement of professionalism. The system professionalism was built upon makes it impossible to prevent a disproportionate effect on the marginalized groups it was never intended for. I would much rather have a policy that promotes safety than professionalism.

The harms of not having a professional-based dress code, however, definitely do not outweigh the benefits. We are part of a society that actively tells women before they enter our institution, and outside of it, that they need to be aware of what they wear. So any form of a dress code, even if it is explicitly gender-neutral, would still disproportionately make women see themselves in the same vein of victim blaming that is forced on them throughout their lives. I think the least we could do is stop that problematic, culturally engrained, projection in our “institution of learning.”

I also have trust in our student body’s maturity level to keep themselves under control. The dress code wasn’t enforced last year, and students’ attire didn’t seem to pose a problem. I highly doubt that any of my peers would echo the Cal Berkeley student and come to school naked. If we can handle a college prep school, we can handle respectful fashion.

AS • Nov 12, 2021 at 1:57 pm

When I was a freshman at Academy in 2012, I got injured and had to wear a massive cast on my leg that went from my ankle to mid-thigh and kept my knee from bending. The only pants I could fit over the cast were athletic running shorts. As I hobbled around on crutches in McKinnon Hall, TWO different teachers (one male and one female) approached me at different times during the day regarding my shorts (which were indeed finger-length, the rule at the time). After getting pulled into each of their offices and made late to one of my classes, I could not help but burst into tears because of the frustration and shame I felt for having to wear certain shorts simply because my cast would not fit in anything else. It is an experience I will never forget, in the worst way. Perhaps they would’ve preferred if I wore a trash bag as pants, since that was the only other thing that could fit over my cast at the time.