[dropcap size=small]W[/dropcap]ith the death toll of Ebola continuing to skyrocket in West Africa, and with alarming statistics bombarding the public (some newspapers are heralding the outbreak as the end of the world), we cannot help but wonder why the epidemic has seemingly spiraled out of control. One of the most conspicuous underlying causes is the utter inadequacy of the public health system in the area. Existing healthcare structures have almost collapsed under the strain of the epidemic, demonstrating that these systems lack adequate funding, staff, materials, and infrastructure.

Although suppressing the epidemic is clearly the first priority for affected countries and the international community, global aid should to continue to support healthcare systems in the area, even after the disease has been eradicated. In recent years, most foreign healthcare aid to Africa has targeted specific diseases, with little regard to debilitated underlying healthcare structures. This has left West African countries unprepared for emergencies, and has given rise to limited and inconsistent care, since a lack of collaboration between multiple donors has produced a redundancy of resources in some areas and a deficiency in others.

One of the primary causes of Ebola’s rising death toll is the paucity of available resources to provide palliative care to infected individuals.

Outside countries should not only provide immediate relief to the crisis, but also help build long-term healthcare capacity in affected countries so they can combat future epidemics. In this manner, the international community can protect itself from health threats. Currently, healthcare access in West Africa is inadequate. Lack of funding and a disproportionately small healthcare workforce are just two of the obstacles preventing inhabitants from having access to quality care. Many foreign funding sources that provide substantial aid to West African countries operate cyclically and can sometimes cut funding. These countries must therefore find alternate revenue streams or divert funds to reduce the financial burden to citizens. Though most primary care services are free, 60 percent of health expenses are paid for out of pocket in Africa.

Additionally, the healthcare system is severely understaffed. The World Health Organization recommends, as a minimum standard, one physician for every 5,000 inhabitants of a geographic area, but many West African nations fall far short of this criteria. Sierra Leone averages fewer than one physician per 10,000 inhabitants. Because these nations have been unable to provide even modest salaries to capable local health professionals, many have emigrated elsewhere. As a result, these countries are forced to rely on temporary foreign healthcare workers, entrenching dependence on foreign aid to bolster flawed healthcare structures. International aid should be geared toward helping these countries assemble and maintain a larger healthcare workforce, and set them on the path to self-sufficiency.

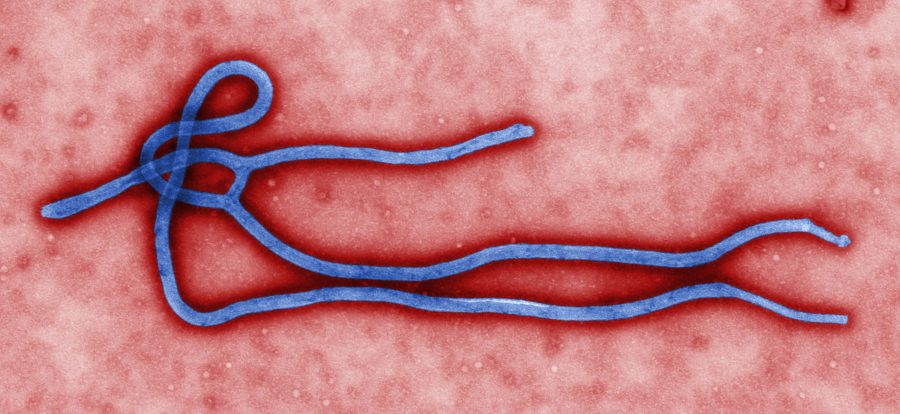

Current obstacles to the elimination of Ebola indicate healthcare deficiencies in West Africa. One of the primary causes of Ebola’s rising death toll is the paucity of available resources to provide palliative care to infected individuals. The trained health workers in West Africa are further discouraged from working by poor conditions and low pay. In some instances, lack of proper protective equipment has prompted healthcare workers to refuse to work for fear of contracting the disease. Hospitals in the area are extremely strained in terms of resources, and are unable to offer care to infected individuals, including pain alleviation and the treatment of resulting conditions such as uncontrollable bleeding from the eyes, ears, and nose.

The international community has a humanitarian obligation to guarantee healthcare to all, and must offer their support to aid West African countries in building sustainable healthcare systems.

Several reasons for the continued spread of disease include a lack of the necessary infrastructure, medical supplies, and personnel to efficiently identify and isolate infected individuals. According to Dr. Anthony Mbonye, Uganda’s Director of Community and Clinical Services, Uganda was able to suppress previous local outbreaks using rigorous surveillance coupled with online reporting systems. However, West African countries like Liberia, the epicenter of the outbreak, have poor internet and telecommunication systems, not to mention insufficient healthcare workers to implement these containment procedures.

Due to the deficiencies of these poorly-equipped healthcare systems, West African governments have resorted to crude methods of containing the disease. Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone have imposed a cross-border “cordon sanitaire” (a system of roadblocks and checkpoints similar to those used during the Black Plague), creating a quarantine zone of approximately 20,000 square km called the “unified sector.” Access to several highly infected areas is barred, except to medical personnel.

The rigid quarantine has failed to effectively contain the disease and has also imposed inhumane living conditions upon citizens. Dire food shortages, dramatic increases in the costs of commodities, and scarce work opportunities due to the termination of trade have made it difficult for residents to survive. The lack of basic necessities has made skipping quarantine a very appealing choice for many hard-pressed villagers. “If sufficient medication, food, and water are not in place, the community will force their way out to fetch food and this could lead to further spread of the virus,” said Tarnue Karbbar, a worker for the charity Plan International. Also, with medical facilities already strained to their limits, people with other serious ailments like malaria have found it difficult to find timely treatment. The disastrous consequences of the quarantine system underscore the absolute necessity of more robust healthcare infrastructures.

The international community has a humanitarian obligation to guarantee healthcare to all, and must offer their support to aid West African countries in building sustainable healthcare systems. West African countries in turn are responsible for upholding human rights obligations and for strengthening health infrastructure so that they are able to provide quality care in the long term and withstand possible future emergencies.