Climate policies worldwide

The world is at an inflection point. As the climate crisis rages across the globe, bringing with it horrendous wrath through various natural disasters and a sense of impending doom as temperatures climb and sea-levels rise, governments worldwide are scrambling to make up for decades of environmentally-damaging policies with new goals and pledges. However, beneath the standard boilerplate of lofty and wordy objectives lies a series of patchwork emission-slashing aims across the world.

So far, the climate crisis has been marked by an uptick in global environmental catastrophes, including hurricanes, droughts, and wildfires. The most well-known examples have included the recent surge of hurricanes slamming the American Atlantic and Gulf coasts, wildfires raging along the American and Canadian West, flooding in coastal cities across the globe from Mumbai to Miami, and debilitating droughts in places like the Sahel desert in North Africa. Such catastrophes have struck up energetic pro-environment movements orchestrated by youth leaders across the world and have forced governments to promise a reduction of emissions and an increase in the usage of renewable energy. Wealthy western nations, like the United States of America and the United Kingdom, have been the target of the most criticism of perceived inaction on the crisis, resulting in the release of lofty new goals and policies last year. Other nations, like India and China, nations on the rise on the global stage, have also been under the spotlight of attention from climate activists. Meanwhile, nations like South Africa have also taken steps toward combating the climate crisis, acknowledging that if the crisis were to spiral out of control, their continent would suffer the most due to the intersection of ongoing social, economic and political woes and disparities.

Part One: The West

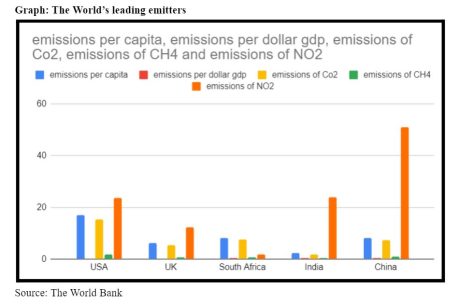

As mentioned before, rich nations such as the U.S. and the U.K. have long come under scrutiny for high levels of fossil fuel usage and middling results when it comes to environmental protection. Recently, however, these governments have tried to change their tune, particularly after the U.S. elected pro-environment president Joe Biden. As of 2018, the U.S. recorded 17.01 metric tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions per capita, placing the nation above all other major industrialized nations in fossil fuel consumption. Moreover, the U.S. also leads such nations when it comes to the release of carbon dioxide emissions, 15.2 metric tonnes per capita, and methane emissions, 1.89 metric tonnes per capita. On the other hand, the United Kingdom, on par with other European countries, reported marginally lower emissions on all categories, with a total of 6.1 metric tonnes of emissions released per capita. Nonetheless, both nations and others across the first world have released lofty goals and aims after coming under unrelenting pressure from activists to do so.

The U.S. recently unveiled a pledge to slash their emissions by 50 percent by 2030 and to achieve a complete net-zero emissions future by 2050. The U.K. went even further, and pledges to slash its emissions by 68 percent by 2030 and to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. In the U.S., these pledges are also backed up by a series of new provisions implemented by the Biden administration, including new EPA guidelines, bans on new oil drilling, and renewable energy provisions in the recently-signed Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. This followed years of pro-fossil fuel and pro-coal policies during the Trump administration, and failed attempts at passing climate reform during the Obama administration before it, despite the former president’s attempts to cap emissions. Overall, the United States has often lagged behind European nations due to the influence of members of congress from coal-producing states, such as Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the leader of Senate Republicans who lead an aggressive effort against President Obama’s efforts to pass a climate bill over a decade ago. Hence, with such members of congress in office, progress in the United States has proven to be a slow endeavor. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson also unveiled his climate plan late last year, which included groundbreaking investments in electric vehicles, offshore wind power, and the use of hydrogen-based energy, all showing that the nation is prepared for a clean energy future.

A report by the Center for Climate and energy solutions stated that the fastest-growing energy source in the U.S. comes from renewable sources, including wind, solar, and hydropower. Most of the nation’s renewable power came from wind and hydropower, though it notes that solar power is the fastest growing source of electricity, an indication that the people of the U.S.are quite progressive when it comes to energy use. Additionally, a separate report from the U.S.Energy Information Administration noted that coal production, known for its notorious toll on the environment, had fallen to its lowest point since 1965, and coal production declined by over 20 percent in the state of Wyoming, the nation’s largest coal producer. Additionally, in the state of West Virginia, the report shows that coal production declined by almost 30 percent over the same period.

All of these statistics show that, though the West and the world has quite a way to go in their fight against the climate crisis, they have made, and continue to make strides when it comes to the use of clean energy across the board, whether through government or civilian action. The United Kingdom’s government reported that their usage of coal has declined from 40 percent to under two percent in just eight years, shocking statistics that bolstered the government’s decision to eliminate the production and use of coal by the end of 2024, just a couple of years away. Moreover, renewable energy reportedly makes up 43 percent of the nation’s total energy use, significantly higher than the 12 percent that such energy sources make up of the total use in the U.S.. Summaritively, these data points emphasize that with a bit more work, the climate crisis could be seriously curbed, even as warnings through severe weather are exponentially getting more frequent and intense.

Some nations in the European Union, like France and Germany, have also fended off criticism from climate activists and recently set in place new climate policies aimed at preserving the environment. France recently established a net-zero emissions goal for 2050 in addition to a climate bill that is intended to slash household uses of greenhouse gases and overall national waste. Germany has taken an even more aggressive tack, promising to cut around 65 percent of their greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and completely eliminating them by 2045, earlier than the United States, The United Kingdom and France. This shows that Germany has clearly attempted to stand ahead of the curve on this issue.

Overall, after years of what activists interpreted as middling or even regressive actions when it came to the climate crisis in wealthy, first-world countries, it seems that many governments are starting to succumb to this pressure, and institute more strict climate policies. Such new initiatives were on display last fall, when the global climate summit took place in the British town of Glasgow.

Part two: Africa

Many agree that Africa will bear the greatest brunt of an extended climate crisis, especially due to its already vulnerable political and economic conditions. The effects can already be seen in desert communities, like those across the Sahel, who suffer from droughts which have led to a depletion of the availability of water and record-breaking high temperatures. A report from the Foreign Policy Research Institute suggested that the climate crisis and the droughts coming with it, could do horrors to African agriculture, further weakening the economic standing of the continent, and increasing the impact of these environmental shifts. This has left more wealthy African nations, like South Africa, to consider proposals that would cut down on their use of fossil fuels and increase their use of renewable energy. South Africa is also the continent’s largest polluter, clocking in at 8.07 metric tonnes of total emissions per capita, further heightening the stakes of reform. At the moment, they have pledged to cut down their overall emissions by around 30 percent by the end of the decade and have pledged net-zero emissions by 2050, on par with western nations like the U.S. and the U.K. These policies were initially more moderate, though have amped up in their intensities in recent years as the crisis has worsened worldwide. Other African nations have also stepped up with climate solutions in recent years, including Nigeria, which has aimed to cut its emissions by around 20 percent over the next decade and has tried to turn the page on their oil-heavy past with a focus on energy sources like solar and hydroelectric. Poorer nations, including Sudan, which contains much of the harshly affected and severely impoverished Darfur region, has largely found its climate policies focused on outside grants and assistance. The United Nations Democracy Fund approved a grant in 2020 pertaining to climate resilient critical infrastructure projects, which the nation will need as natural disasters continue to strike the region.

What richer African nations, like South Africa and Nigeria, and poorer African nations like Sudan do going forward will determine their continent’s immediate fate as they find themselves in the belly of the beast of the climate crisis. Also interesting to watch will be the role of richer nations, like China, in their investments in Africa as the climate crisis rages on. China has been recently amping up their investments in the region, particularly on infrastructure, which has lead many to trace such investments to a broader strategy of Chinese influence, and some wonder if investments in climate resiliency will be the next frontier of such influence. According to data, China has more specifically been amping up trade relations with nations such as South Africa and Nigeria, the richest African nations, displaying their strategy of influence front and center.

Part three: India and China

Meanwhile, in South Asia, one of the most rapidly developing nations in the world, India, is actively working on progressive climate action to cut down on both pollution and emissions, among other actions. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has led these initiatives, particularly on anti-pollution initiatives in the Ganges river. India currently emits 2.25 metric tonnes per capita in total, lower than other heavily populated countries, though still significant given India’s large population. Their emissions of nitrogen dioxide, however, are a bit higher than many western nations at 23.95 metric tons per capita. India has pledged to cut their emissions by 45 percent by 2030 and aims to reach net-zero emissions by 2070, amounting to more modest proposals than western nations, though still significant given the size of India’s industries. Additionally, the government has pledged to reduce pollution, including in the Ganges river, one of Modi’s landmark policies. Modi also promised to add 500 gigawatts of renewable energy over the next decade, in a large effort to curb the usage of fossil fuels in India and to seek cleaner alternatives. However, India is one of the world’s largest consumers of coal, with recent reports suggesting that coal makes up around 70 percent of India’s total energy consumption, signaling the work that lies ahead. Moreover, coal mining is a significant industry in India, showing the economic consequences of a sudden withdrawal. However, India’s emission pledges combined with their renewed focus on power sources like solar and wind plant seeds of optimism for the world’s second-most populous nation.

As for the world’s most populated nation, China, which emits around 8.17 metric tons per capita yearly, a large amount of scrutiny has been placed on their efforts to combat the climate crisis, as China grows in global power. First, China’s toll on the environment has often been on par with industrialized nations in the West, and sometimes even bigger. China is the largest emitter of nitrogen dioxide emissions, releasing 50.85 metric tonnes per capita, not to mention their significant emissions of carbon dioxide (7.4 metric tonnes per capita) and methane (0.88 metric tonnes per capita). Additionally, China is by far the world’s largest consumer and user of coal, complicating efforts to protect the environment in the nation. This metric has been exacerbated by reports that the Chinese government has turned to an amped-up usage of coal in recent times as their nation has faced a devastating lack of electricity, which has had detrimental effects on the worldwide efforts to combat the climate crisis. China has hiked up their usage of coal by 6 percent from last year, a consequential move that experts say has the potential to single handedly warm the earth by a percentage point. Nonetheless, China has pledged to cut their emissions by 25 percent by the end of the decade and has charted a path that incorporates a net-zero emissions pledge by the year 2060. On top of this comes the fact that, despite their vigorous use of coal, China is simultaneously the world’s largest user of renewable energy. This is spearheaded by their rapid expansion of power sources like wind and especially solar energy. Numbers like these have left the West scrambling to catch up, showing the contrasting nature of China’s relationship with the climate crisis: both a coal-guzzling villain and a clean energy trailblazer.

What India and China do with regards to the climate crisis will have global implications and reverberations. This is due to their large consumption of coal, which has been proven to have detrimental effects on the environment, and their growing prominence in the global economic and political stage. In other words, as these nations develop and advance their economies, how environmentally conscious they are will likely determine the effectiveness of global efforts to combat the climate crisis. This could also play into their overall rise on the globe stage; successful and large investments in modernizing their economies and expanding their spheres of influence are definite possibilities, and the climate crisis could provide a linchpin onto their policy efforts to achieve such a scenario.

Conclusion

Overall, the world remains at a crucial crossroads between saving the planet or heading into a frightening fate of oblivion. In the West, signs seem to be positive, with increased civilian usage of renewable energy and new transformative government initiatives and goals that, if achieved, would truly elevate the world’s relationship with the environment. However, it is yet to be seen if the West will be able to ward off the ghosts of an industrialized past heavily reliant on the burning of coal and the toxic use of fossil fuels. As for Africa, it has now become clear that the continent’s top economies, nations like South Africa and Nigeria, are starting to take the climate crisis in an extremely serious manner, with the recognition that their continent will suffer the most from an extended environmental catastrophe. The question now remains whether the world’s collective efforts are enough to ward off devastating events in the short and medium-term in extremely vulnerable regions like the Sahel. In Asia, where the world’s largest coal users lie, it is positive news that both India and China have committed to increased usage of renewable energy and have pledged to curb their emissions over the coming decades. However, it is yet to be seen if those initiatives will be able to overcome both nations’ reliance on coal, which has acted as a dark cloud floating eerily above the world’s climate fight.

At the end of the day, however, the consequences of inaction on the climate crisis will have impacts on life across the globe. Action today will dictate the future of regions like the North American gulf coast, the desert regions of Saharan Africa, coastal cities across the globe, and island nations like the Maldives and Tuvalu, who are bracing themselves for the complete submersion of their countries unless the world can muster enough change to shift their trajectory towards a better direction.

Abhishek is a deeply engaged member of the Albuquerque Academy community, part of several government and politics-focused clubs and activities. For the...