AA Should Do What it Can…

Editor’s Note: Readers brought to our attention unclear language in an earlier version of this story which gave an impression that was not intended by the author. As an editorial staff, we evaluated the critique and found it to have merit. We have worked with the author to clarify the language in this current version of the article to address the concerns of our readership. We always welcome written responses to our articles and strive to publish a wide range of viewpoints especially on challenging topics.

The 2020s have included an overdue rejuvenation of the civil rights movement. The result is a spotlight shining upon the elements of institutional racism that have been embedded into our culture. For the better, it is about time this light shines upon our school. As my classmate and Advocate opinion editor Neil Mahto points out, it is our obligation to combat this racism that continues to exist in our community. Neil’s sternly written call to action was necessary. I was inspired by the issues he brought up, but I think that some of his solutions may have unintended consequences, and I question the ways in which we, as a community and an institution, should go about solving these problems. In this article I will cover my concerns in response to Neil’s criticisms and suggestions, as well as share my ideas about how we can cautiously approach this challenging issue through education.

The first of two themes I would like to bring up is the extent to which we should blame the Academy for having racism on its campus. To blame an institution built in a racist country within a racist world for being racist is unfair. With racism systemically woven into our country’s history, it is difficult to expect the Academy to somehow construct a gate that prevents it from entering campus. As the article mentions, “Not only is our school as an institution not racism-free, but our school as a community is far from it as well.” While this statement is correct, there is simply no way for a high school to be immune to racism. Racist biases are cultivated from someone’s early years, family life, social media, peer groups, and countless other factors. Sadly, I have doubts that any school has the ability to create a completely racism-free community that exists within a systemically racist environment. To fault a school for its failure to accomplish this impossible task is overly critical.

Instead, the Academy should be measured by what it does to educate people on systemic racism, implicit bias, and how we can move forward into the world to be a part of the solution. For example, this year, and last year, while learning about U.S. history, my teachers made sure that my classmates and I understood that the racism that existed in our country, continues to exist, and is a factual matter not a matter of opinion. In fact, I have had teachers condemn some of the racist, classist, and deplorable beliefs of former president Trump. Likewise, with my advisor I have talked about the plague of recent Asian hate. These teachers, and their impact on me and my fellow students show that the leaders of this community, through education and awareness, are part of the solution, not the problem.

Head of School Julianne Puente has been criticized for limiting her role to helping “the children in her sphere” rather than fulfilling an “obligation to help everyone [she] can.” It is an unrealistic thing to ask that we help everyone we can all the time. When we walk down the street on a cold day, perhaps with a warm beverage in hand, or bundled together by an excessive amount of layers, and walk right by a homeless person, we are not doing all that we can to help them. Although some may not want to admit to it, that is simply not the world we live in, let alone an economic possibility. The fact of the matter is that if the Academy tried to exist for everybody, it wouldn’t exist for anybody. Instead, we should recognize that Ms. Puente influences hundreds of graduating students each year, sent out into the world to do their part in making it a better place.

The Academy may have a different purpose and mission, but at heart, the school is just another business. Even as a non-profit, the Academy nonetheless has a budget that relies heavily on donation-based endowments. Therefore, to say that the Academy is elitist and classist is to say that a restaurant that only serves paying customers is elitist. The economic reality is that the Academy can only provide education in return for enough money to keep themselves afloat. With the Academy as a private school giving an advanced education built on highly developed infrastructure and programs, comes the downside of funding the endeavor.

The question that necessarily follows is: what should the Academy do to combat institutional racism? Certainly, whenever Academy has the chance to condemn racist language, such as the use of the n-word, along with any other insulting, bigoted speech, it should immediately react strongly and swiftly. In fact, it is the Academy’s prerogative and duty to take disciplinary action. However, with such a policy, the question gets asked as to what defines deplorable speech. The line has to be set somewhere, and we risk being too radical in what we prohibit. The article references “Blue Lives Matter” merchandise being worn like it’s a fashion statement. If a student were to be forced to remove a “Blue Lives Matter” hat, would someone have to remove a “MAGA” hat– a hat representing Trump, a figure who stands in front of Blue Lives Matter advertisements, and other “anti-Black Lives Matter” material? With the exception of preventing hate speech, it is the job of the students to decide what is politically “correct,” not the institution. If anything, the Academy should foster beneficial conversations and greater understanding of politics within the student body. It should educate a student about the history and implications of their beliefs, giving them a greater foundation to stand on as a democratic citizen.

Finally, the proposal to fill Academy’s classes to a proportional demographic level parallel to that of Albuquerque, with acceptance based on a lottery, is rather unique. I think it is a great way to strive for a more racism-free community. However, there are many troubles that it would lead to. As many commented, if students were chosen by a lottery system, then their credentials and knowledge would not matter to the application process. These students would bring uneven levels of education with them and no curriculum would be able to account for their different needs. Likewise, the Academy would soon find itself in a financially stressful situation. With students being randomly selected by a lottery, there would simply be too many families unable to pay the current tuition. Although our tuition is expensive, so are the facilities, faculty, and programs that make the Academy nationally renowned. One must take a realistic approach and concede that if the Academy were to open its gates and outreach, it would suffer a loss of tuition revenue, and thereby a diminution in its ability to deliver the very good it most values.

My points all come from the perspective of a privileged white 16-year-old boy in America. Thus, my experiences in the Academy are distinct. The reason I write is not at all to challenge the idea that racism is at the Academy, but instead to discuss how it should be handled. A totally racism-free school in the midst of an institutionally racist culture is an unrealistic expectation. Thus, the assessment should not be whether the Academy has been successful in eliminating racism entirely. Instead, it should be measured by how far it goes to acknowledge the topic and implement methods to combat it while staying financially solvent and academically elite. As long as they continue to pursue that goal, by giving students summer reading books revolving around prejudice, teaching our full history, and allowing students to debate the roles of crucial issues such as racism in our community, then they are heading down the right path.

Academy’s Race Problem

An Ambitious Mission

Albuquerque Academy has a race problem. If you scroll to the bottom of the school’s website, you will find that “Albuquerque Academy is an independent, college-preparatory day school for students in grades 6 through 12 and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, creed, religion, national origin, ethnicity, or disability in admissions, the administration of its educational policies, tuition assistance, athletics, and other school-administered programs.” While the intention is there, the execution lacks. Not only is our school as an institution not prejudice free, but our school as a community fails to be a safe space for diverse groups.

Albuquerque Academy inclusive community allured me. My elementary school, in hindsight, did not sport a welcoming enviornment for a little brown kid. All of the more than 30 teachers were white. I was skeptical the Civil War was fought over states’ rights. Ads for Albuquerque Academy seemed Elysian. They featured smiling, Ivy-bound kids, some with melanin, and an intriguing curriculum, seldom finding itself antithetical to racial equality. Fifth-grade-me was ecstatic when he got that acceptance package in the mail. Five years later, I’ve started to look beyond AA’s faded facade.

Institutional Diversity

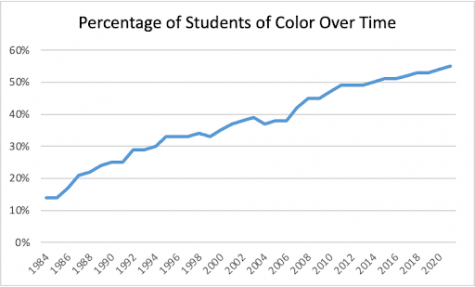

Over my years here, I have come to see these diversity claims as exaggerated. As the graph shows, we have improved dramatically since 1984 in terms of the percentage of our student body that identifies as minorities, a figure now touted at 58% in admissions literature. My conversations with Mr. Gloyd and Ms. Puente also demonstrate the complexities of collecting and evaluating such data.1.5% of students solely identify their race as Black. However, 4.5% of students identify as Black when you include multicultural and multiracial children. The city of Albuquerque is about 3.31% Black. For Native Americans, about 1.2% of students identify solely as Native American while 4.6% of students use Native American as one of their many racial identifiers. Albuquerque is about 4.7% Native American. These figures are encouraging and appear to be on an upward trend. However, despite the relative success in recruiting students of color, our school is far from being racially or ethnically egalitarian.

A lack of institutional diversity can still affect the well-being of the student body. One student, who preferred to stay anonymous, told me “I do think the lack of diversity impacts me. Being [one of the] only fully Black kids in our grade does suck sometimes. It’s like a lot of my problems, whether they be about hair texture or other things, [are] hard to talk about because no one can relate to me or truly understand how I feel.” The dichotomy between the school as an institution and the school as a community is critical. While both can be problematic, it seems the school is making improvements as an institution each and every year, with attempts at improving diversity and inclusion, while the school as a community is not.

The community’s prejudice, however, ties directly to the school as an institution and as a center for learning. Prejudice isn’t innate and should be edified. The two issues of prejudice in the community and prejudice in our institution are inherently linked.

Problems in Curriculum

We claim to be different from those American institutions that are built on a history of racism: the police department, healthcare, criminal justice, and many more. Albuquerque Academy is one of the best high schools in the country, but we are perceived elitist. APS student often label us “the rich white kids.” Despite a prima donna attitude, Albuquerque Academy has yet to combat that stereotype. We are responsible for the uninviting culture we sport.

Take the Asian community for example. Asian people at our school are not exempt from bigotry. In history class, our westernized curriculum paints Asian nations as failed states. It’s not until sophomore world history that we learn that Asian and African modern economic problems stem from European and American imperialism. American exceptionalism is overtly present in the way the school teaches history. In 6th grade, I was taught that the bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima were panacea. I remember in-class discourse about about justifications – as if killing millions of people is ever justified. As 11-year-olds we were taught that the nuclear weapons on innocent civilians resulted in peace and saved lives, rather than the spectacle of genocide that they were.

New Mexico is a community pervaded by indigenous and hispanic culture. White people’s feelings aside, the United States as a whole as a requiem of indigenous torture and European colonization. I applaud Academy for devoting an entire year of education, 7th grade history, to New Mexican and Indigenous history. Yet, there remain a number of students whose cognizance of our relation with tribal nations severely lacks. The educational has a responsibility to further recognize this community ignorance as a result of shortcomings in curriculum. Our community attitude highlights the prevalence of American exceptionalism in the classroom.

To continue, one of the scariest days every year for each little brown boy and girl in this country is 9/11. We’re told by our parents to stay alert and hide our cultural identifiers. During history class on this day in the U.S., many feel the need to hide their faces in the back of the classroom. We learn that 9/11 was an attack on our beloved country by a group of religious extremists. Academy teachers certainly deliver a better message but still fail to counter the dominant narrative. What we fail to learn is how that day amplified Islamophobia in our country. Muslim comedian Hasan Minhaj said, “We felt like our love for this country was under attack.” What we fail to learn is how Ronald Reagan and the CIA funded the terrorists that ultimately committed the horrific acts on 9/11. For how long will we let little kids blame their own for 9/11?

A Problematic Culture

The community in general has upheld xenophobia. Bigots are quick to point out inhumane Chinese dog eating practices, but ignore the American agricultural industry. The bias towards white culture at our school and in our society remains obtrusive. The hidden goal is not to stop inhumane dog eating practice but rather to paint one culture as primitive compared to another. Coronavirus has only amplified animosity towards the Asian community, with many on campus choosing to point the blame towards anyone from the continent. I promise you that asian restaurants will not give you coronavirus. People are using any means possible to point the blame towards Asian people.

In a similar vein, the n-word has been reduced in our community. It’s a word that denigrates Black people and has historically been used to identify them as personal property. The word is toxic, offensive, and hurtful. In my opinion, and as I wrote previously, the word should be restricted to use by Black Americans. Yet, non-Black Academy students throw it around like it’s sarcasm. It’s not an uncommon occurrence. The lack of Black students and faculty adds fuel to the fire. There’s no one holding people accountable for misusing this harmful word. While we certainly have gotten better about using the word, many students still use it frequently. While the faculty may be blind to this, the fact that Academy students feel that it is OK to use the word is partially our as a school’s fault for not properly educating them on the word.

To not understand indigenous culture is to understand the state that supports you. I, too, am at fault, lacking proper awareness of cultures other than my own. You, me, and the community have a cultural obligation to engage respectfully with cultures that aren’t our own. Administration could support this by bolstering awareness of opportunities to do so while also improving cultural comparative literature in English classes and widening the scope of history classes.

In recent years, some students have sported “Blue Lives Matter” merchandise like it’s a fashion statement. Blue Lives Matter is a protest to Black Lives Matter and a symbol of hate. After the death of George Floyd, some students were quick to point out his past transgressions as justification for his murder. Classmates ridicule others who are trying to be a part of the solution. While many in our community are activists for race issues, the number that actively contribute to these issues is appalling. Many express the old “13 percent of the population, but 50 percent of the crime,” chestnut referring to a cherry-picked statistic on Black crime, as a valid reason for racial disparities in arrests and police murders. The message that statistic is conveying is that Black people are inherently more crime-prone than other Americans, and confuses a trend tied to poverty with a trend tied to race. Above all, it’s the job of community leaders to stop the spread of misinformation, particularly those that stem from bigotry and hate.

Community Responsibility

Albuquerque Academy must not only hold students accountable for blatant racism, but they must also incorporate things like racial bias amongst policing and harmful stereotypes into their curriculum.

The school should exert more effort freeing up money for financial aid. They should look to students of color for advice on how to make the community more accepting or consulting with SDLC or other student-led affinity groups.

I would like to make two drastic suggestions to the administration that can be made immediately. One being to ditch admission testing and reconstruct the process altogether. I propose that the administration adopt a lottery system with a quota. This quota would align with the race demographics of the city at the time. Admissions testing is an unfair and inaccurate way of judging intelligence and compatibility. A lottery system prevents the underserved from being shot down by admissions testing where they are put up against more affluent candidates. Admissions testing unfairly favors white and rich students. We have a responsibility to give a good education and opportunity to those who have been denied it.

The second suggestion is to stop playing the national anthem at school events. The Star-Spangled banner had been edited immensely before it came to the form we know it today. One lyric that was removed was No refuge could save the hireling and slave. The lyric was meant to threaten African Americans who fought for the British in exchange for their freedom during the war of 1812. While the lyric was removed, the anthem was still written to glorify a country which at the time enslaved people for the color of their skin. The very institution the anthem was built upon was founded on the practice of slavery. It screams a forced loyalty to a country that has not ensured fair or just treatment to everyone.

Accountability and Aspirations

Head of school Julianne Puente told me that “we do not have an obligation to help everyone,” and that she will help “the children in her sphere.” She went on to explain that we did not have the resources available to do so. While that may be true, I vehemently disagree with her original statement. Everybody has an obligation to help everyone else that they can. The sphere that Ms. Puente is referring to is a sphere of elitism. What we should be doing is widening that sphere. However, we are no better than anyone simply because we can afford a fancy institution. We are no better than anyone because the color of our skin is lighter.

This issue too is very nuanced because the school simply does not have the funds to help everybody, but we cannot operate on the idea that we must only help the people in our “sphere.” In fact, Ms. Puente said, “The Academy will always fall short of its mission.” I whole-heartedly agree, but that doesn’t mean we should abandon the mission altogether.

As a student of color who has attended the school for almost six years now, this is far from the truth. Simultaneously, I sit in position of privilege compared to many and encourage those who feel marginalized to take a stand for their peers. The administration must do what they can to address the issues: hold students more accountable, ditch American exceptionalism in the classroom, change the narrative and stigma associated with the school, and adopt a fairer process for admitting students. For now, we as a community can work together to stop hatred and bigotry. We can hold others accountable and, at times, even hold ourselves accountable. We can make minorities feel included and more comfortable to simply exist at Albuquerque Academy. Maybe then, we can claim that we do “not discriminate on the basis of race.”