Bio Students Participate in Genetic Research

Breeding new lines of flies for researchers

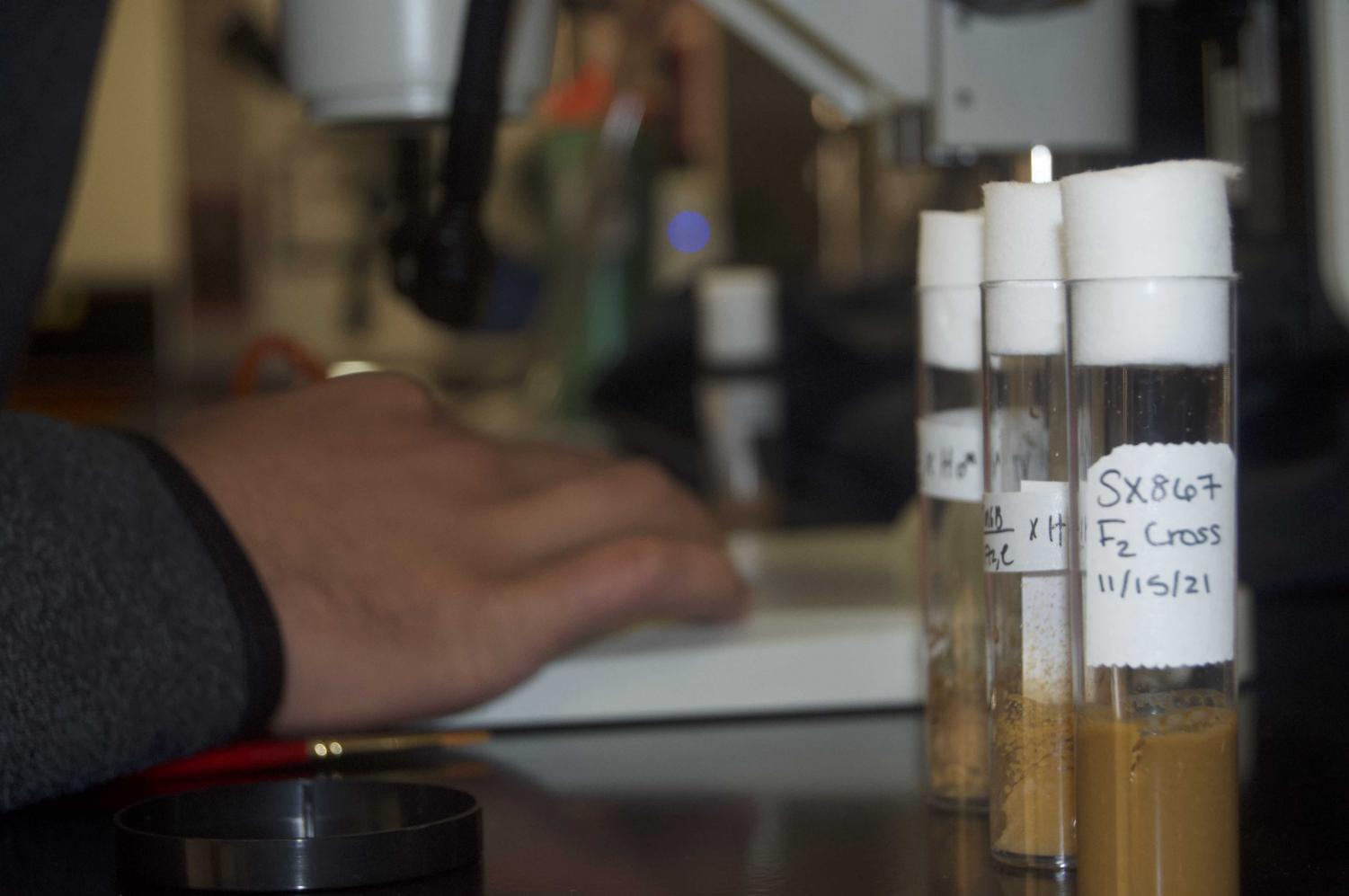

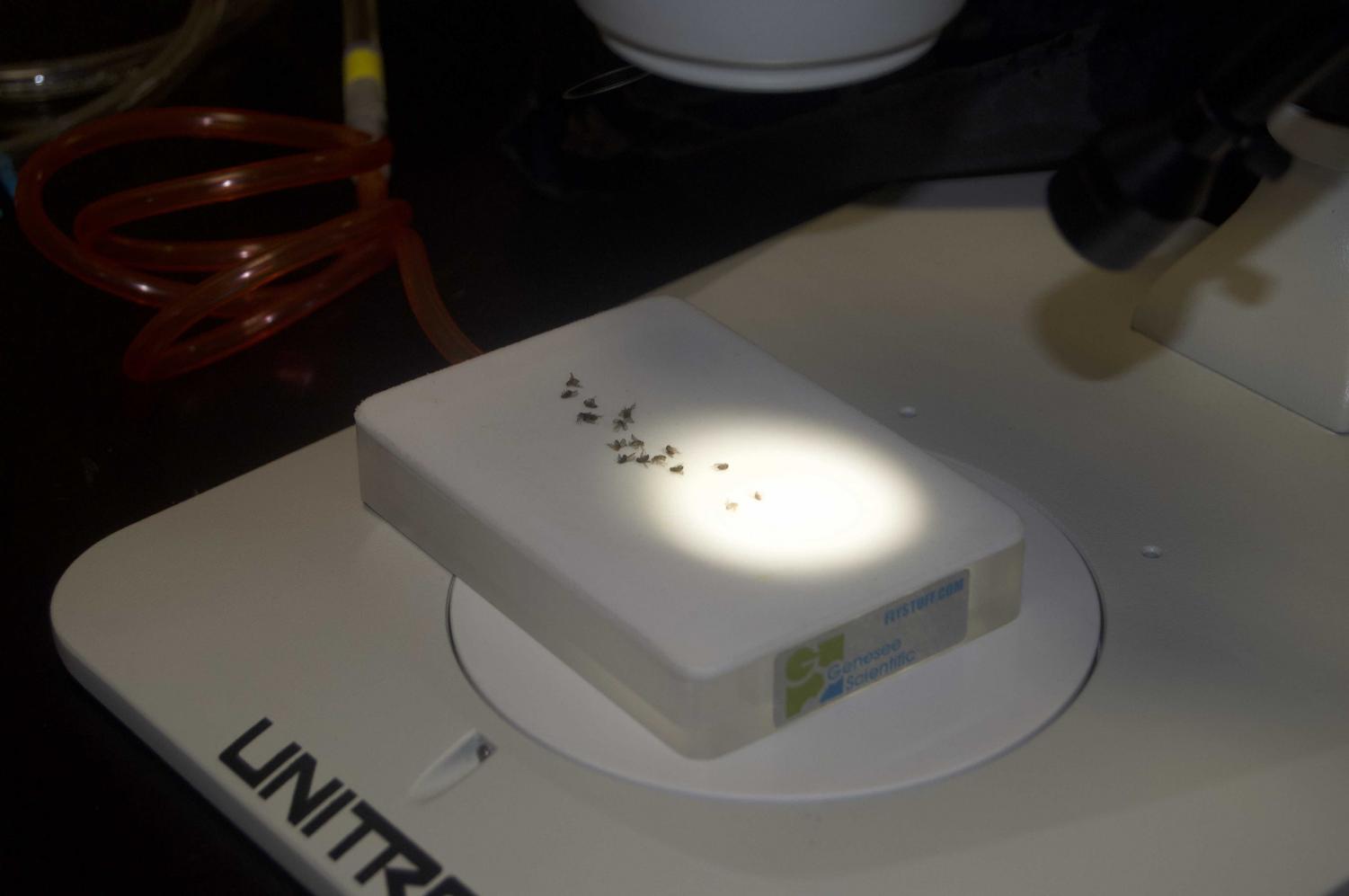

Students hunch over microscopes, adjusting knobs and squinting until an image comes into view, one of the dazzling DNA lines of fruit flies. For the very first time, Academy is offering a hands-on, “real science” course that branches from the revolutionary Fruit Fly lab initiated by Dr. Seung Kim and Dr. Lutz Kockel of Stanford University. So what exactly is the point of the class? According to Meg Reese, one of the two teachers of this brand-new course, “we are doing a series of specific [genetic] crosses with specific flies in order to create an end product which is finally coming out right now. We’re generating these transgenic [genetically modified] flies, which will theoretically have a new genetic code because they’ve got a jumping gene inserted somewhere new in their genome.” Essentially, students will generate unique fly lines by sequencing fly DNA.

Instead of being in the classroom all day, students are “in the lab every single day,” notes Reese. She continued, “Sometimes it’s the entire class period and sometimes it might just be half the class period. And then we’ll cover some content as well. But for now, this first part of the course has been very lab intensive.”

Deciding it was “an opportunity [they] couldn’t pass up,” the two Academy teachers, Reese and AP Biology teacher Miranda Fleig began a rigorous training program during the summer of 2021 to teach them how to teach this brand-new course. “It was pretty intense,” says Reese. “We were in the lab and getting trained by the experts and learning how to identify all these characteristics on the flies and how to do the molecular components and even how to dissect larvae.”

According to Dr. Kim of Stanford, who recently visited campus, much of early science education is taught by “reading and recitation and regurgitation,” with no “resemblance to what a scientist does, which is to ask questions, to think about the right questions to ask, and to face a complete unknown, unscripted activity.” While Kim and Kockel have been experimenting with fruit flies’ DNA since 2001, they decided they wanted to “shift the paradigm” and begin teaching by doing, just as Academy’s motto, scientia ad faciendum (knowledge for the sake of doing), suggests. It seemed obvious to Kim, in retrospect: after all, you wouldn’t “learn to play an instrument only by reading textbooks about it.” Soon after this idea, he and his team came up with an idea “to co-opt a classroom for fly genetics.” The first year the class was implemented, at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire in 2012, was “pretty much an unmitigated success.” Since then, ten more schools have adopted this class.

So is it an unmitigated success at Academy? From Fleig’s and Reese’s perspective, absolutely. According to Fleig, “the students really enjoy being in the lab. It’s been fun to teach them how to identify the different characteristics of the flies and learn how to take care of them.” She added, “it’s also really beneficial and enlightening for them [students] to be thinking about what’s going on with the chromosomes, at the molecular level of what they’re seeing in the flies.” Jullian Chanda ‘22 would agree—he says, “My favorite part of the class is managing the fly vials: the reproduction and selection of useful traits.” He mentioned an activity a “normal” science student would never do: “We’ve named the fly morgues, the conical flasks with alcohol in which we dump the unconscious flies, things like ‘morg’em freeman’ (a pun on… Morgan Freeman) or ‘the chalice of eternal egress’.” Of course, it wouldn’t truly be an experimental science course without a few hiccups. Chanda adds, “The main challenge is reacting to non-ideal circumstances. When nature gives fly types that don’t conform to the predicted results, it’s a pain to track and figure out if you messed up breeding the wrong flies, or it’s just some random variation you can’t find a cause for.” Stephanie Good, Science Department Chair says that difficulties like this are “part of the whole scientific process. And I think that the kids are actually learning a lot from seeing those mistakes and trying to figure out why something has happened.” Another difficulty the students have encountered is the schedule. Mrs. Fleig notes, “it’s nice to have that longer block. But not meeting every day is hard.”

Nonetheless, both teachers agreed that they “would definitely like to see more experimental classes” implemented at Academy. Good added that they are “looking as a department to integrate more hands-on inquiry-based lessons into regular classes.” When asked about what kinds of students they recommend take this class, Fleig said she would invite “students that are happy working through problems and don’t give up easily” to take this class. Reese added that “if there [are] students who think they might want to do molecular research, it’s a great opportunity to try it out.”

Finally, I asked what the ultimate goal was for this class and the research of fruit flies. A cure for diabetes? Cancer? For the Academy, the new transgenic flies they create every year will “contribute to Stanford research, but some of these lines could go to the national fly repository, where researchers all over the world can order that line of flies and use it for more experimentation.”

The same question was posed to the Stanford researchers. But upon being asked if their end goal was to cure diseases in the pancreas, Dr. Seung Kim and Dr. Lutz Kockel looked at each other, puzzled. “We are humbled before that four-letter word starting with C-U-R-E,” says Kim. “That means different things to many people,” he continues, sharing a grin with Dr. Kockel. “I mean, if you break a bone and you set it, and it is healed, and you never think about it again, completely regain function, that’s a cure. Right? Many of the diseases we are interested in like diabetes and cancer, have what I would call operational definitions of that [a cure]. Our goal is to understand the biology underlying processes that are very clearly related to diseases.” But seeming unsatisfied with his answer, Dr. Kim offered one last response. “I would say the answer to that would be eventually. That’s what we hope it will be.”