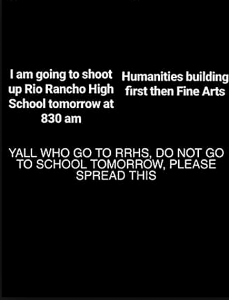

“I am going to shoot up Rio Rancho High School tomorrow at 8:30 a.m. Humanities Building first then Fine Arts.” The message, sent out at night on Feb. 20 over Snapchat through a fake account, was simple, sinister, and, after the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting left 17 dead, all too believable. Within minutes, the threat had appeared on countless Snapchat profiles, along with a note begging Rio Rancho students to stay home. The next day, hundreds of parents kept their children away from school and possibly imminent danger, while police, notified by dozens of calls from concerned students and parents alike, patrolled both of the threatened buildings throughout the day. Thanks to increased police presence and a decrease in student attendance, no violence occurred. Social media had apparently saved the day.

Or so it seemed. In reality, the threat was a hoax, now under investigation by Rio Rancho police, and one that had spread like wildfire through the channels of social media. It is likely that almost every high school-aged Snapchat user in northern New Mexico saw the message, many screenshotting and reposting it. It bears a marked resemblance to Rio Rancho’s last “threat,” which occurred in 2014 when, a week after a Roswell school shooting left two critically injured, anxious students misconstrued an innocent Instagram post as a threat. Over 50 percent of Rio Rancho High School’s student body did not attend school the next day. And New Mexico is not alone in the frequency of hoax incidents following school shootings: in the days following the Marjory Stoneman Douglas massacre, at least 56 schools nationally reported hoaxes or threats. As dozens of teachers and friends involved with the Florida gunman bemoan their overlooking of signs that violence was imminent, it seems that the rest of the country is constantly on guard for these same threats to the point where “jokes” in poor taste can cause hundreds of students to stay home.

Social media has changed the way that the country perceives violence in more ways than one. Videos captured in the heat of the moment humanize events and bring empathy to the carnage. After the Orlando Pulse nightclub shooting in 2016, Snapchat videos portraying the violence went viral, showing a crowd shifting from joy to terror in a matter of seconds as the gunman opened fire, killing 49. Acts of violence are no longer relegated to lists of the dead and solemn obituaries; instead, they are commemorated in heart-wrenching videos, often only seconds long, capturing the fear and injustice of such events. Oftentimes, entire political campaigns are based around social media, such as the massive nationwide school walkout that occurred on Feb. 21 when thousands of students rallied to advocate gun control. An Instagram post or a Snapchat story can bring together millions of students across the globe and organize a generation to rally for a cause.

However, social media can also be a perverse way to spread more sinister messages. The shooter at Marjory Stoneman Douglas, Nikolas Cruz, was reported to have a prolific Instagram account in which he posted photos of his firearms and disemboweled animals, as well as a YouTube account on which he wrote that he “was going to be professional school shooter.” Although the FBI deemed his digital profile to be “very, very disturbing,” it was only after the shooting that reports made to the FBI—which were apparently never acted upon—surfaced. In the wake of the shooting, dozens of incidents were reported in which teenagers made ominous videos that threatened violence similar to the carnage in Florida, including multiple students who were arrested for threats made over social media. One such incident occurred in Belen, where a 16-year-old published a message vowing that fellow Belen High School students would “see his wrath” and that he would “be the next to go down in history;” the student was quickly tracked by police and arrested, after which he claimed that he had only made the threat to observe public reaction to it. The “copycat phenomenon” is especially common in the United States, where high gun ownership rates have given teenagers unprecedented access to firearms, especially those with parents who do not keep their guns in safes or other protected areas. With this in mind, it’s easy to see how a hoax threat, like that at Rio Rancho High School, could be easily interpreted as a true danger to students.

Although social media has the power to bring together groups and increase awareness of disasters and acts of violence, it can also be the very medium in which mental illness and anger can develop into these same acts. With the relative lack of patrols on social media, both activists and future perpetrators can thrive, making them sites of danger for both sides. And, while increased awareness of threats can help to stop the path to carnage in its tracks, it can also lead to frustrated police officers and school administrators who find themselves responding to empty threats rather than actual danger. Social media must be used with caution and, perhaps, given greater controls that would ensure safety for users and bystanders alike. In the Internet’s “no-man’s-land,” change must come from below in order to prevent bloodshed from occurring and to protect American citizens and students.