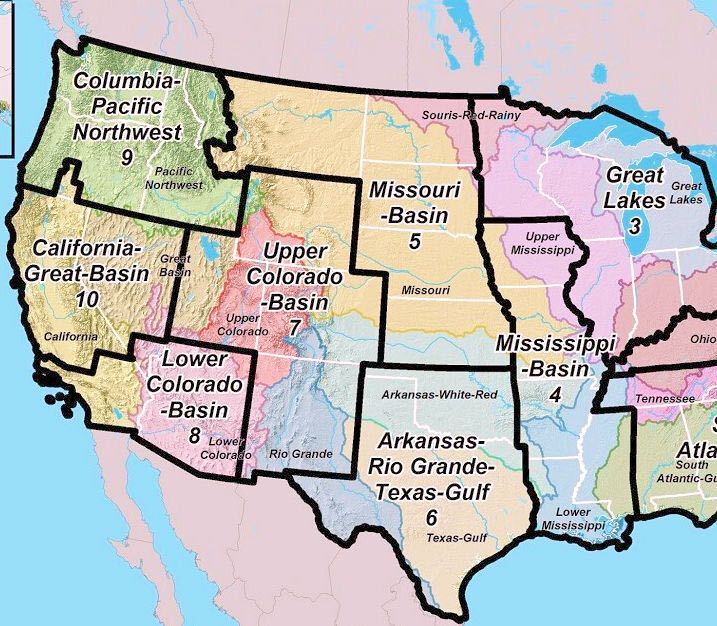

Southwest States Negotiate to Reach Deal on Colorado River Water Consumption

Where are we in the process, and what happens if a deal isn’t struck soon?

Public domain. https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/map-region-7-upper-colorado-river-basin-0

Since 2000, the Southwest has been engulfed by its worst drought in over 1,000 years. The drought has led to extreme strains on water resources, particularly for the seven states that depend on the Colorado River: Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. These states failed to come to a unanimous agreement to limit water usage from the river by January 31, the deadline set by the federal government. Tensions are high as each state depends on the Colorado River to support both their cities and agricultural sectors. This has made reaching a deal that benefits everyone increasingly difficult, especially since California, the state that diverts the most water, has failed to agree to the proposed solution put forth by the six other states. However, the issue of water extends far beyond a single deal as the Southwest continues to face more and more challenges from the megadrought damaging the region.

Do we have a deal?

Colorado, Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming have all agreed to a plan that would drastically cut usage of the Colorado River’s water supply down to only 2 million acre feet of water, decreasing current usage by about a quarter. The agreement was reached after the Biden administration threatened to inflict its own cuts.

However, California has refused to agree to the emergency plan, opting instead to put forth a plan of its own, which offers an alternative to California cutting down on its own water usage, which they say could hurt public safety and health; instead, more water would be taken from various reservoirs. The state believes that the proposed water cuts are too extreme and has also said that other states should bear the brunt of water cuts because California is supporting the largest amount of people and agriculture. The other states have failed to agree to this plan because it would force them to impose even more of their own water cuts, does not officially account for evaporation, and would lead to unbalanced amounts of water in reservoirs like Lake Powell and Lake Mead, which are already rapidly depleting.

In addition to California not agreeing to the current proposal and the subsequent stalling of negotiations, there have been many other conflicts as well. For instance, the water from the Colorado River supports over 40 million people. Many are worried that cutbacks could negatively affect the multibillion dollar agricultural industries in each of the states because “protecting the interests of everyone, cities and farmers from Wyoming to Mexico, is nearly impossible,” as Alex Hager from NPR explained.

In addition, upper basin states – Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah – feel that lower basin states – Nevada, Arizona, and California – should be making more cuts because they use much more water. For instance, in 2021, upper basin states used about 3.5 million acre feet of water whereas lower basin states, along with parts of northern Mexico, used upwards of 10 million acre feet. One proposed solution to the usage disparities came in December of last year, at a meeting held in Las Vegas, Nevada. There, representatives discussed Arizona, California, and Nevada decreasing water usage enough to compensate for evaporation as water moves downstream. In exchange, upper basin states would agree to divert more water downstream to dams and reservoirs, sending water to the lower basin states. The plan eventually fell through because California felt they were having to cut back on their water usage too much.

A 23-year long megadrought

All of these issues have arisen because of the megadrought that has dried out the Southwest for the past 23 years. UCLA geographer Park Williams said, “It’s extremely unlikely that this drought can be ended in one wet year.” Many researchers also believe that climate change has exacerbated the consequences of the drought. Temperatures on average have increased in the last 20 years because of global warming, which has increased water evaporation. This, in turn, means that soil often dries out quicker than it used to. Thus, more water is lost before it ever gets to be used by soil and plants. As a result, the drought’s consequences have increased exponentially.

Challenges facing New Mexico

For our state in particular, the drought has spurred two massive issues – water conservation and forest fires. The proposed deals would impact water conservation because New Mexico gets about 10% of its water from the Colorado River, most of which is transferred by the San Juan-Chama project, a series of tunnels and dams that delivers water across the state. New Mexico would have to reduce the amount of water that is diverted through this project. This would put more strain on the state’s agricultural sector, which depends on the water from the San Juan-Chama project during the late months of the summer, especially in years with below average snowfall.

Another impact of the megadrought has been the increased amount of forest fires. In 2022 alone, upwards of 800,000 acres in New Mexico burned. More than 300,000 of those acres came from the Calf’s Canyon/Hermit’s Peak Fire, which was the largest wildfire in New Mexico’s history. Based on the snowfall – or lack thereof – received this winter, experts think this fire season could be even more destructive than the last.

In addition, farmers, ranchers, and other agricultural workers – as well as the average New Mexican – may end up being negatively impacted no matter what gets passed. In New Mexico, agriculturalists depend on water from the Colorado River to support crops during the hottest and driest parts of summer. Without it, prices of crops could rise.

Also, due to the drought, many New Mexicans live in fear of running out of water. For instance, small rural towns, like Magdalena, New Mexico, are unsure how long they can continue with the current water supply. According to various climatologists like Dave Dubois, “It could be 100 years, or 80 years, or 60 years [before the water runs out]— we’ve got a limited amount.” However, New Mexico has been inconsistent with their water recordings historically, so no one has a solid idea of how much water New Mexico really has left. One thing is certain, however: many New Mexicans have begun to suffer from having too little water. It has hurt town expansion, caused farmers to cut back on their crop production, and led many small towns to make cuts on anything that could diminish drinking water supply. So even if a plan manages to get passed, it still does not answer the question of whether it will be enough to solve the problems caused by the megadrought in New Mexico and beyond.

A member of The Advocate since 7th grade, Elizabeth enjoys writing news, school and local, and arts and culture articles. She can't wait to help writers...

Jade • Feb 27, 2023 at 8:35 am

Great reporting Elizabeth! This is a concerning topic and I’m glad you are getting the word out. It’s inspiring to see you people engaged.