An Academy Land Acknowledgment: Who, What, and Why

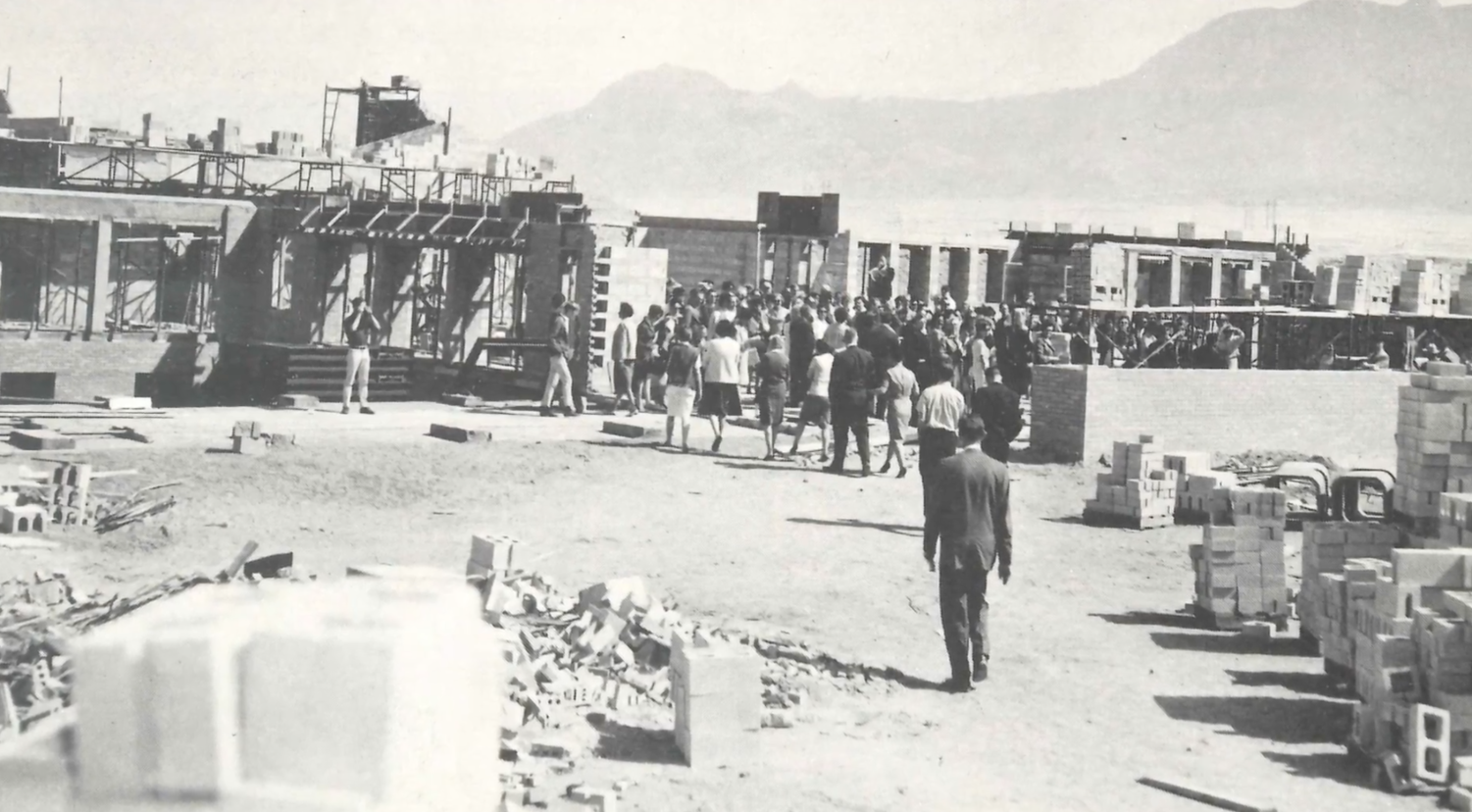

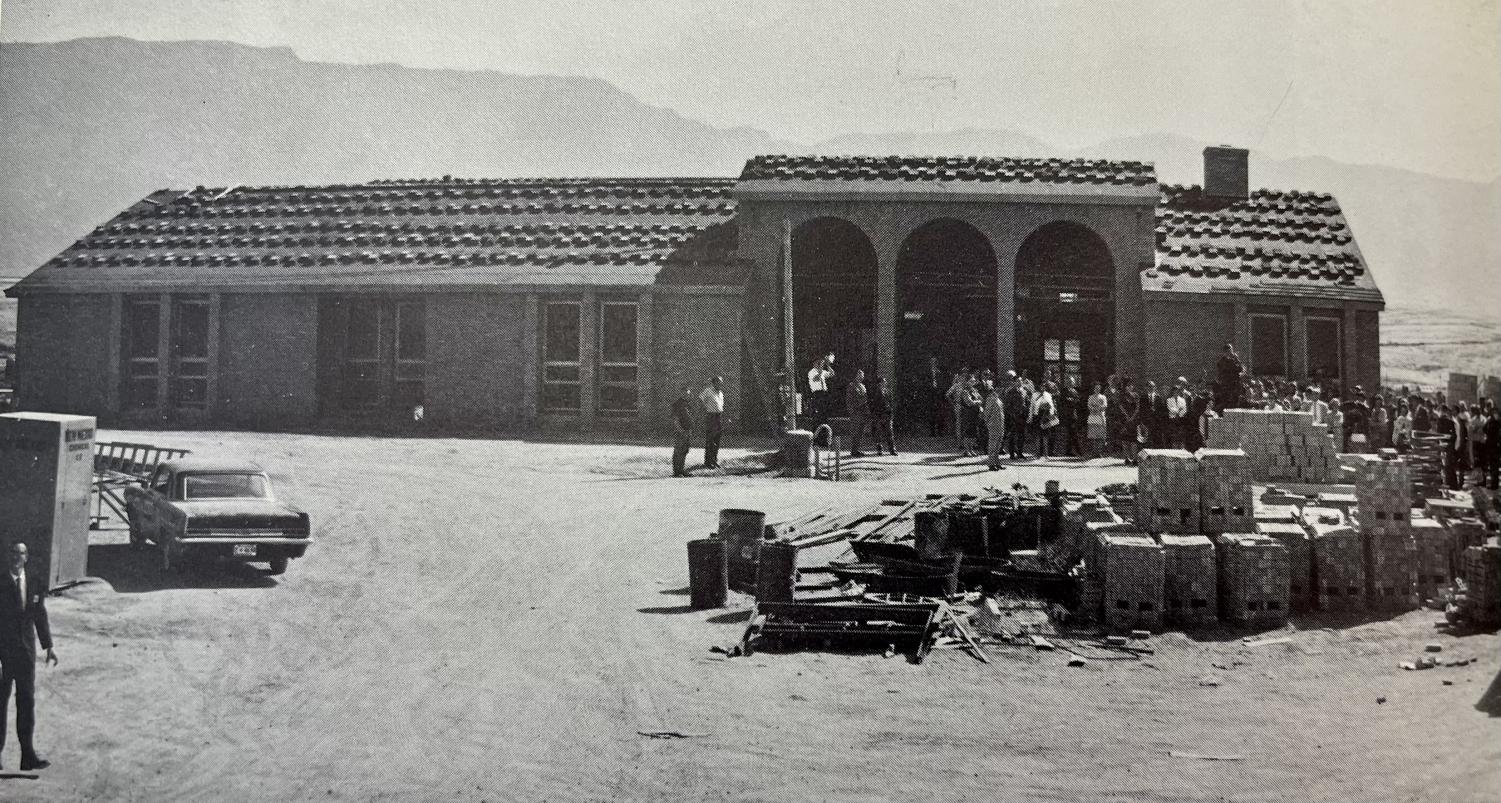

“I believe, quite simply, that there is a very real danger for all of us associated with the Academy: the danger that we will casually, complacently, carelessly and even smugly accept our fine new school without once reflecting on how little we have done, individually or collectively, to obtain it or even to deserve it.” —Headmaster Ashby Harper at the groundbreaking ceremony for the Albuquerque Academy campus (May 15, 1965)

1965 groundbreaking ceremony for the new Albuquerque Academy—Headmaster Harper gives the first public remarks on campus.

Albuquerque Academy is in the process of creating a land acknowledgment that would recognize the Tanoan Pueblos, specifically the Sandia and Isleta Pueblos, whose original homeland our campus now inhabits. Diversity, Culture, and Belonging Coordinator (DCB) Peter Gloyd and College Guidance Officer (CGO) Jessica Becenti initiated the process and are now working with the Board of Trustees and Head of School Julianne Puente. The acknowledgment will be spoken at large school events and serve as a public display of respect for the history and stewardship of the land we learn on. However, Native student leaders feel unimpressed and disheartened by their limited involvement thus far.

Becenti, who is herself Diné and Comanche and holds a B.A. in Native American Studies, is actively authoring the statement. One draft has been presented to Puente and a small number of students. A new draft is in the works. Our school will have a land acknowledgment when a draft is approved by Puente, student leadership, and ultimately the Board of Trustees. In terms of what this will look like, the administration pictures a brief but meaningful statement. “We want it to be transformative,” says Gloyd. “We want it to be something that is useful for the community. It’s something that hopefully validates and affirms students in our community and also heightens our responsibility.”

This process started last year when Gloyd was approached on his first day as DCB Coordinator by a faculty member wondering if the Academy has or ever has had a land acknowledgment. Recognizing an opportunity, Becenti and Gloyd then teamed up to produce one. Since that point, it has been a slow process toward finalizing a statement. Working with colleagues at UNM in the American Indian Student Services Department, Becenti is writing a second draft. “Our land was taken from us; it was stolen from us.” Becenti stated, “I want the school to acknowledge that and respect where we sit, respect where we walk our feet every day and respect our mother earth.” In her mind, as an Indigenous employee, the statement represents “where we stand” on Indigenous inclusion as a school. Becenti explained that finding the balance between too aggressive and too light of a statement is a crucial part of this project. “We don’t want to have a land acknowledgment just to have a land acknowledgment.” The administration shares that sentiment and has been supportive of the process, according to Becenti.

New Mexico has a vibrant Indigenous population, with Albuquerque alone having the 7th largest urban Native population in the country. Yet Indigenous Americans are underrepresented and often their voices are silenced. Land acknowledgments are meant to honor those mistreated in the process of getting to where we are today. “We’re an educational institution so we want to tell the truth and also learn from the truth,” Gloyd told me.“It’s past due,” said Gloyd. “We [want to] have an accurate account of history…the facts in terms of what we’re acknowledging are not new.”

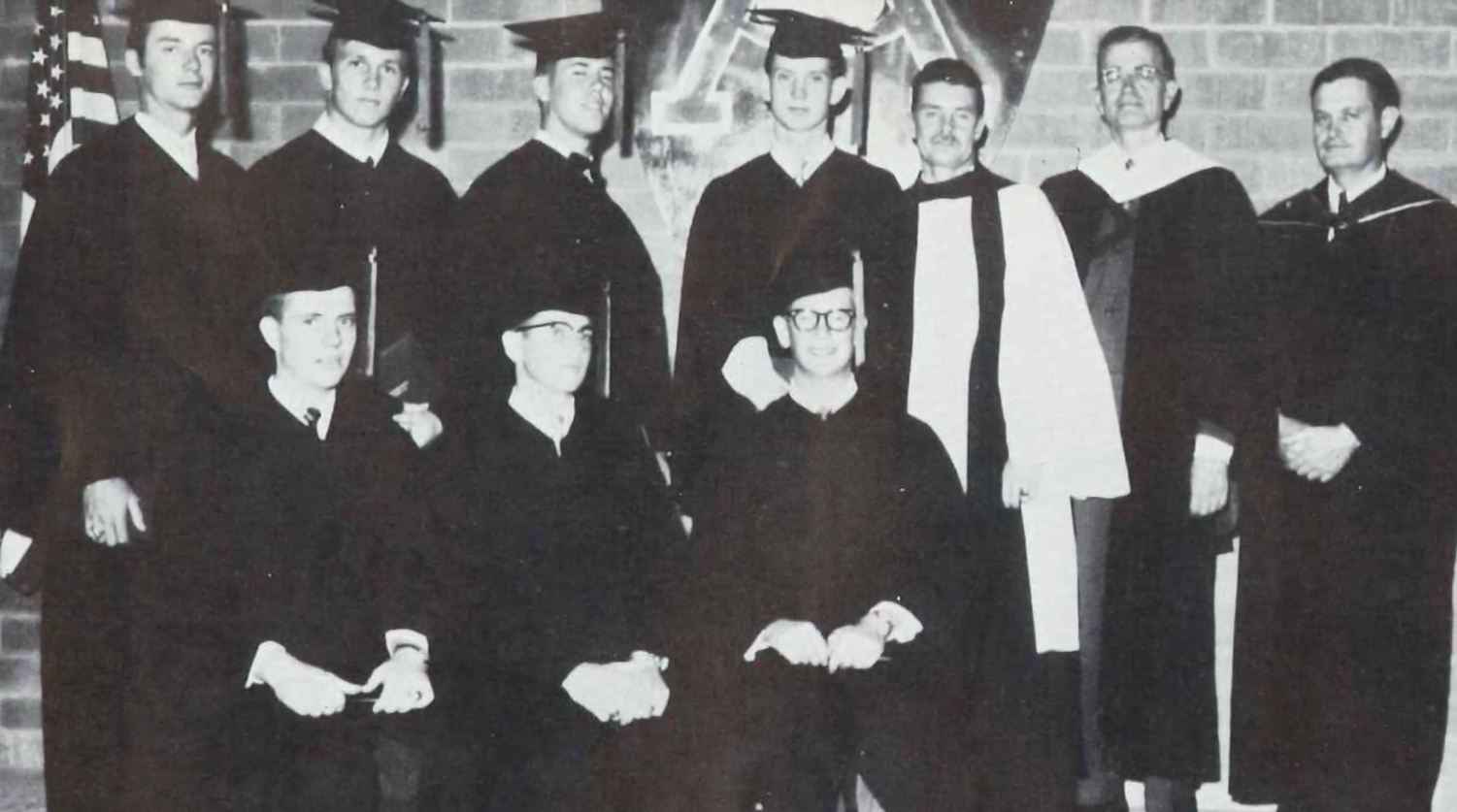

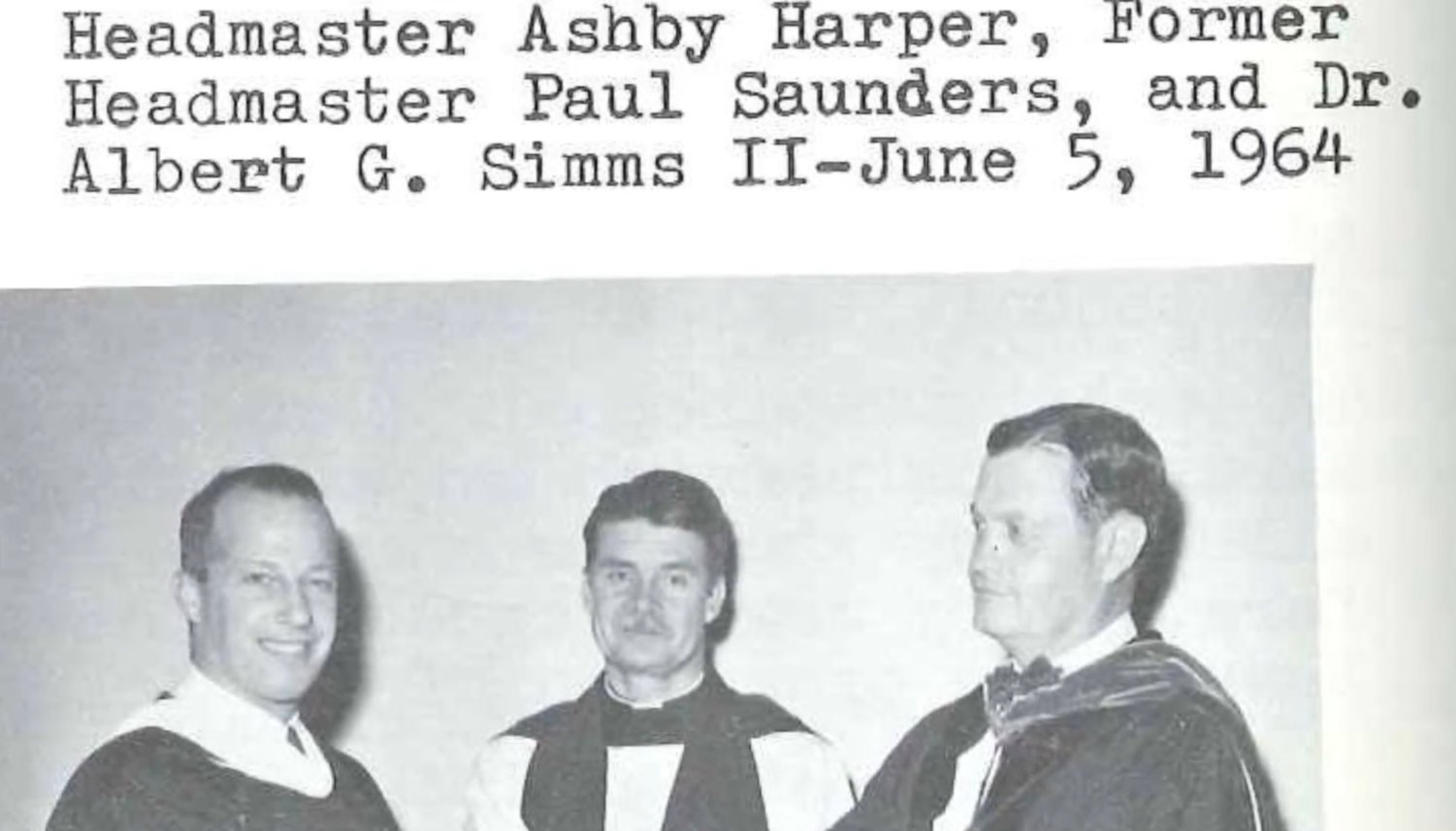

The Albuquerque Academy for Boys was founded in 1955 by William S. Wilburn. The school moved to its northeast location in 1965 after the institution received a large portion of the Elena Gallegos Land Grant from the Albert G. Simms family. The Western portion of that land, spanning from Wyoming Boulevard to the Rio Grande, was sold to create the school’s first endowment fund. Much of the land east of Wyoming was sold in a series of deals in the 80s. Our current campus was built right in the middle. Gloyd made the point that “we often think of that original land as a ‘gift,’ but that also wasn’t necessarily someone’s to give in the first place.”

Land acknowledgments began becoming a worldwide movement for public and high-profile institutions in the 80s. Countless universities and metropolitan areas have public statements meant to recognize those communities who lost their land by force through colonization. Many educational institutions have a statement, including UNM. The city of Albuquerque itself has an approved city-wide acknowledgment, the original stewards of the Albuquerque area being the Tiwa—a group of Tanoan Pueblo tribes—also known as the Tigua.

Land is complicated. Acknowledging its history is complex due to millennia of Native history and the centuries of dispossession, disenfranchisement, and displacement that Native Americans have endured. Most Indigenous groups no longer live on their traditional rightful land, and many places in America have been occupied by multiple Native nations over the course of history. There is a lot of education taking place amongst the board and school leadership in order to understand the nuances of history. Gloyd believes that “we all are in a place of learning and growing in this area,” a sentiment echoed by both Becenti and Puente.

While Becenti and Gloyd write, the board discusses, and students await a new draft, Puente is overseeing the issue. “I am not an expert with land acknowledgments,” she expressed. She has met with leaders outside of the Academy to explore what the purpose of a land acknowledgment is, and she feels strongly that it is not a process she is equipped to drive personally. “I am not from New Mexico, so I also want to learn from the institutions and people around me,” she says. “Land is sensitive…I look at my role as a steward of the land of the Academy.

I believe in respecting those who have come before me.” Puente says her view on land was shaped by her time in the Middle East, and though she is not experienced with the issue of land acknowledgment in America, she is “fundamentally in favor of the process.”

She has seen a draft and requested a second draft with a few suggestions. In terms of its usage, Puente commented: “there have been ideas that an acknowledgment needs to be read before every class and I don’t subscribe to that. I do think it should be acknowledged before major events like convocation or graduation or those kinds of events as well perhaps the opening faculty meeting.” Puente continued: “I did not want to be the author. I felt that I should be an editor. And there are other voices that should be in it I thought, you know, and I can see someone saying ‘Oh, that lacks leadership.’ And I think that is a demonstration of respect because I could copy one from something else, but that’s not an authentic acknowledgment.”

While the statement remains unfinalized, most involved parties agree that a land acknowledgment is a beginning not an end. While there are no specific plans for what comes next after the acknowledgment is finalized, Gloyd hopes for a “cultural shift” or “enhancement” toward further mindfulness and responsibility for stewardship of the land we operate on. For specific action, he envisions continuing Academy’s outreach to Indigenous communities, recruiting more Native students to our school, and working to create a more supportive and positive community for Native students to flourish at Academy. Gloyd has ideas including after-school programs, growing the Multicultural Summer Honors Program, finding ways to reduce barriers such as transportation for students coming from surrounding pueblos, connecting with the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, and collaborating with the education directors of tribes, pueblos, and nations in the surrounding area. Gloyd has no shortage of thoughts on what comes next.

To Becenti, an acknowledgment is a pathway toward making the Academy a space where all students belong and feel welcome. “I would like to see a school that is more diverse,” envisions Becenti, “This isn’t the real world. I’m hoping to bring the real world into our community.” To her personally, the next step is seeing more people of color on campus and in employment. “It’s hard for a person of color who is in a white institution. To think: Well, I gave up my leadership in my community, I gave up my language, I gave up a chance to where I could better myself in my culture at another school, to be here. I don’t want students to feel like that. I feel like I want them to have a space where they could express their cultural belonging and cultural expression here on campus. And I feel like there’s a lack of that here. And I think this year, there’s some sort of presence, and we’re hoping to continue that too.”

In Puente’s mind, next steps are unsure. “We have made connections with different pueblos and other Native organizations to encourage students to come and apply, and as the population grows within the Academy, I just think we’re a healthier school in that way.” She feels the ‘how’ of a land acknowledgment is relatively simple, but the ‘why’ and the next steps are more complicated. “I think I can answer the ‘why,’ the next steps I am unsure.”

“I know this is the right first step,” she said, “but step two, three, four, and five, I don’t really know…I’d rather listen and ask the question myself and then figure out the answers that we need.” She shared: “I think people expect the first draft to be perfect and it’s not and that’s how you end up having discussions and educating people about it and understanding where people stand and, you know, I have been a little surprised at the ‘well how can it not say this’… like, oh my gosh, why are we not simply having some discourse about it.”

But, who is in the conversation? Though the Native American Parents Council did not respond to requests for comment by press time, members of the student affinity group—the Native American Chargers for Change (NACC)—shared feeling left out of the process. Isaiah Nash‘23 stated: “This is a very, very small first step in the process of making amends for the genocide and theft of land necessary for an institution like Albuquerque Academy to exist—the fact that not even this can get through is a bad look.”

Co-President Jenny Blackwell ‘23 elaborated: “Land acknowledgements are a symbol of respect and understanding. This land was here long before us, and it is important to recognize that. Tribal cultures teach us that we belong to the land, not that the land belongs to us.

The land acknowledgement is an important step in recognizing that our school belongs to the land, and that we respect the Indigenous cultures who lived here, taught here, and learned here long before us. These Indigenous communities are still here; we respect them and we respect the land.”

Fellow Co-President Zola Ortiz ‘23 commented: “This land acknowledgment is long overdue. It is definitely a step in the right direction, but to be honest, it is really hard to comment on this land acknowledgment since I have only seen one draft briefly at the beginning of the year. As the Co-President of the Native American Affinity Group at Academy, I hope our group will be given a meaningful opportunity to provide thoughtful comments on the land acknowledgment draft. I really look forward to being more involved in the process.”

Their statements provide insight into the reality of the process and were passionately voiced. At the same time, administrative members spoke from an opposite perception. “[We want to] find a way to have a version that incorporates as many voices as possible,” Gloyd commented. “I think we’re open to including more student voice or community voice, and it’s a little challenging too, you know, the more people you have in the room [the more] have to come to a consensus. So I think where we’re at now is like, how do we invite people in a fair, equitable way, but also in an effective, productive way?” He said the DCB leadership team as well as Puente are looking at who will be involved moving forward. “We want to make sure that we have representation and just a good collection of voices and perspectives,” Mr. Gloyd commented.

On the same topic, Puente agreed that student voices should be involved on the topic. “I asked that they be involved more,” she stated, before continuing, “I think it’s also important to understand that this policy will live beyond when they graduate. It’s larger than them, it’s not frozen…I’d like some more voices,” she said, “that’s why the first draft went back with these recommendations. But I didn’t think it was smart to simply give kids a blank page. Like there needs to be some framework on it. And that they’re not the sole authors…I think shorter is better personally. And I would also like those discussions to involve the ‘why’ it’s important and how it would be used. That’s all.”

The student group continues to feel left out of the process, though the administration shared big plans to involve them. Gloyd shared that the acknowledgment is likely ready for another iteration; student leaders within the NACC hope their voices will be included in a fuller manner this time around.

The process has been in the works since early last year. Many student leaders have shared discomfort with the lengthy timeline. “We don’t want this to be something that we [only] have great intentions for,” said Gloyd. He shared that the administration wants to avoid a situation where “we put it out there and it has a negative effect or harmful effect on members of our community.” He wants to make sure “we’ve taken the time to reach out to community members. There’s only so much time and it’s definitely something that’s very important to us, but it’s hard to find that dedicated time,” he continued.

When asked about the timeline of the statement, Puente shared: “I have to say I kicked it off really early last year. And, you know, when you’re working in one area, you’re not working in other areas…I’m not as much in a rush as I am want[ing] the process to generate a little bit of momentum and have some drafts…I would love to have Convocation next year as maybe being a kind of goal on it…You know, maybe it’s for the Native Month, I, I don’t know, for next October we talked, I don’t know what that would be like…I hope sooner rather than later.”

Moving forward with no set deadline and a seemingly growing frustration from the Native student community, one cannot be sure how this will all play out. For now, a new draft is in the works and both students and school leadership are hopeful about the end goal.

As Co-EIC this year, Halie is thrilled to be leading The Advocate. Since beginning their career in student journalism in sophomore year, they have developed...

Hammad Irshad • Feb 7, 2023 at 9:14 pm

Very well written and detailed article.

Dean Jacoby • Jan 20, 2023 at 5:25 pm

I am impressed by this article. It takes a very complex topic and gives a lot of air and voice to many of the different constituencies involved and affected by it. I also want to commend the administration and the work of DCB–Mr. Gloyd and Ms. Becenti–for doing the hard work required to create a meaningful, representative, and inclusive statement.

In the little bit of experience I have around this issue it is, as Ms. Puente stated, the beginning of a way for our community to recognize the differences between people at and in some way connected to the Academy and the changes that a community must go through when trying to be reflective of all members. As Ms. Weinstein points out quite eloquently in her comment.

It might be interesting for people to know that Canadian Universities are required to have a land acknowledgement. You can go to any university’s website and type in land acknowledgement.

I have also been very impressed by the University of Michigan’s land acknowledgement. Each department has crafted their own statement based on their intellectual lens and the history of the land for the university being “offered” to the state by the Anishinaabeg nations living in the area. They make an acknowledgement at every gathering above a certain size at the school.

Last, more locally, I found the Davis NM Scholars statement to be quite compelling.

I encourage interested folks to google some of those other acknowledgements as links are not permitted in comments.

I look forward to the Academy’s own statement and the continued work of championing the gifts of people from an ever more inclusive set of identities.

Michelle Weinstein • Jan 20, 2023 at 9:28 am

Excellent article, Halie. Reading about the land acknowledgement process hits very close to home as many of us hoping for a pronoun policy for the last year have felt many of the same things regarding timeline, who’s included in the process, and how we make progress. Land acknowledgements serve an important purpose. They remind everyone on campus that history matters, that people matter and that the schools sees everyone. It shows respect. I hope it is completed soon. These acknowledgements, policies and programs matter. The quote at the beginning by Ashby Harper is a brilliant and powerful reminder of who we should strive to be as a community.