Exhibit Review: La Malinche

Albuquerque Museum couples history and art in a mysterious tale

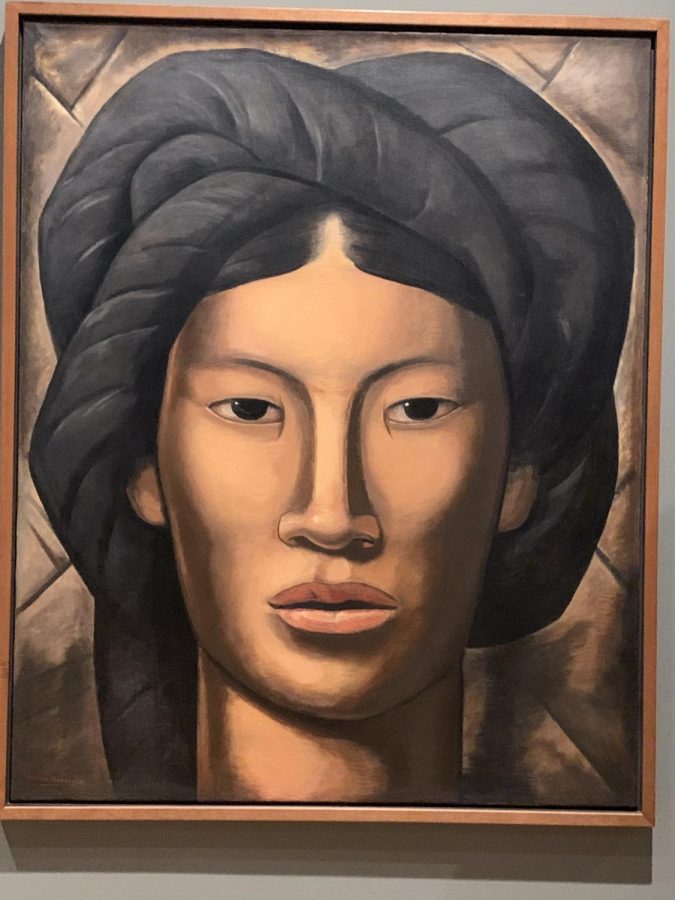

La Malinche by Alfredo Ramos Martíne

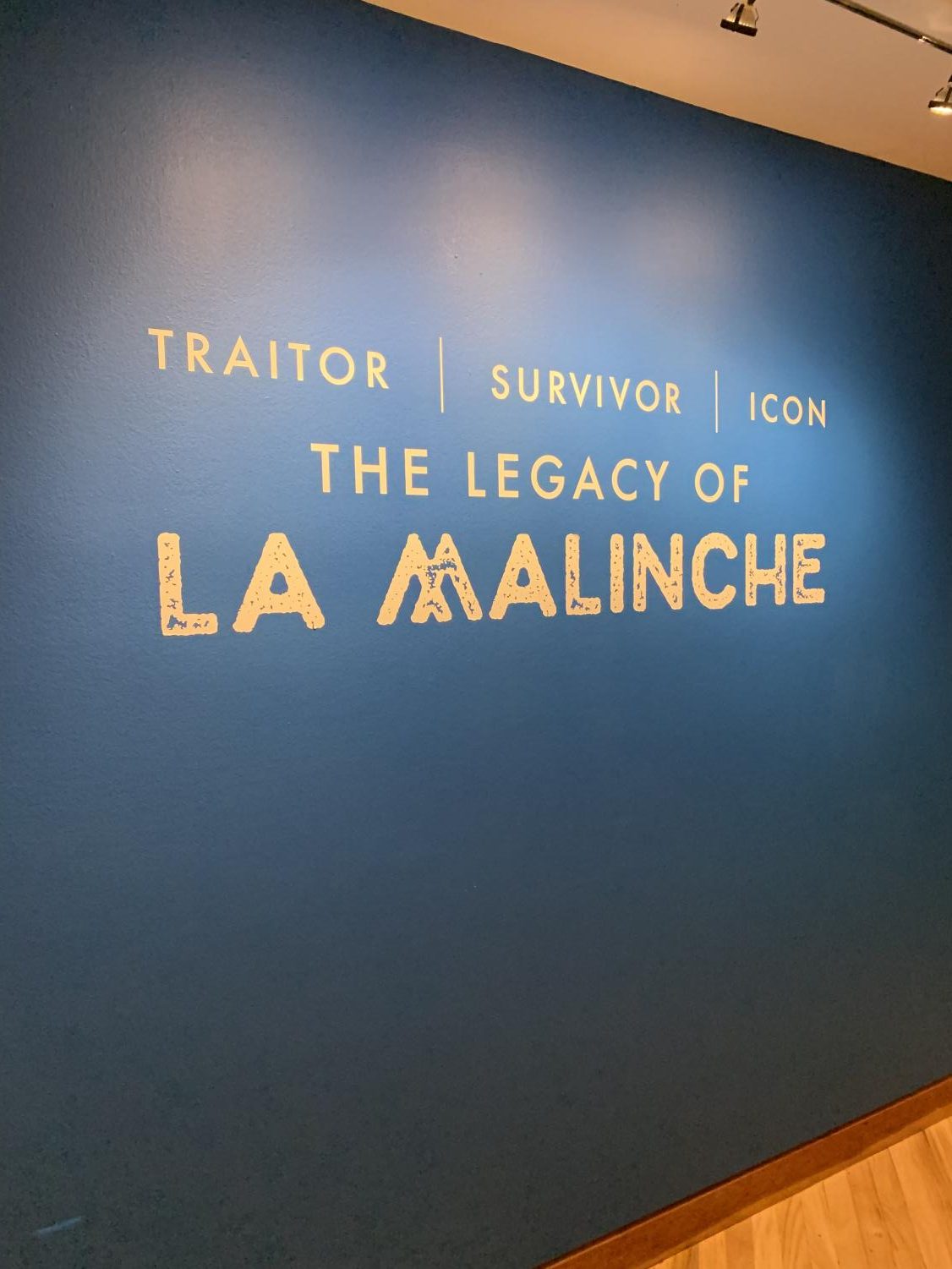

The Albuquerque Museum plays with the complicated reputation of the cultural, religious, and historical figure, La Malinche, in its exhibit: Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche, on display from June 11th to September 4th. Malinche, the indigenous interpreter to Hernán Cortés, later was adopted by numerous Chicana artists in their works. Malinche’s identity is and was often interpreted as a defiance against not only the structural racism, but also against the machismo culture that these women artists could relate to. Many of these artists, most New Mexican, are featured throughout the exhibit. The Denver Museum, the organizer of the exhibit, places Malinche as relevant to both Spanish, Mexican, and Indigenous history, but also as a symbol of Chicana identity. Being in the center of the Spanish Conquest of Mexico (1519-1521), Malinche has had her life and identity scrutinized for hundreds of years. Since history and mythology are often subjective, this exhibit provides a collage of different artists across many years and places. Doing so, the viewer leaves with an understanding of different interpretations as well as the knowledge to form one of their own.

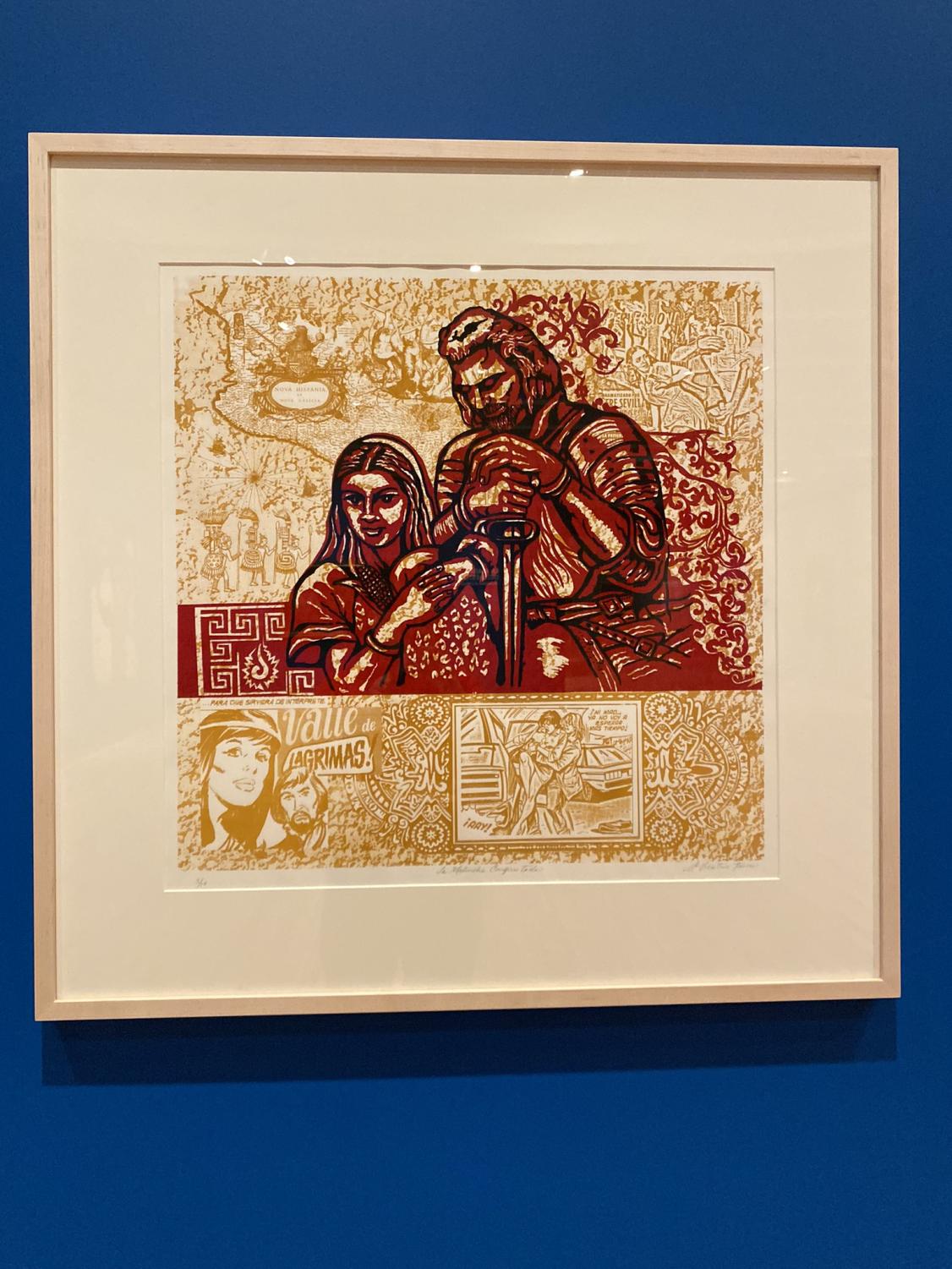

Upon entry, the exhibit leads with the general history of Malinche’s life, providing an overview that gives context to the later, more elusive pieces. An important and multi-part piece Codex #2 Delilah: Six Deer: A Journey from Mechica to Chicana (1992 – 1995), displays a skillful storytelling and overview of Malinche’s tale. Although her background and exact role in history are somewhat ambiguous, Malinche was known to work with and for Hernán Cortés, a Spanish conquistador, as an interpreter and aid during the Spanish Conquest of Mexico, and later a mother to their son. Sold into slavery as a young girl, Malinche’s familiarity with both the Nahua (Aztec) and Maya indigenous groups helped her survive.

The exact relationship between Malinche and Cortés has been debated since the 1500s. Some historians argue that Malinche abandoned her roots to join him as a traitor, while others claim she was forced into the relationship. Her enigmatic identity has provided a tool in various artworks highlighted in the exhibit. The pieces use her character to portray Chicana oppression and with it, the remarkability of overcoming and connecting with culture, privilege,power instability, and the rebellion against suppressive reputations. LA MALINCHE by Judith Hernandez exemplifies the intersectionality of all these aspects into her piece which plays on each interpretation of La Malinche in La Lotería cards, a game specific to hispanic culture.

The exhibit concludes with a focus on modern-day Chicana embodiment, specifically with photographs of New Mexico Hispano and Pueblo communities performances of Matachín dancing by Miguel Gandert. In the story-telling dance, La Malinche is played by a young girl who guides Monarca, representing Moctezuma, the ruler of the Aztecs, and is performed in Bernalillo. This event is depicted beautifully and classicially in the exhibit as a reminder of the present and local influence of La Malinche. Her relevance to our community is reason enough for any New Mexican to visit, but the discourse over legacy and identity that is present throughout the exhibit is why I personally would urge any reader to visit the Albuquerque Museum before this exhibit closes.

Lily, or Lilith, '24 is the Advocate’s 7th-grade editor, working with our youngest writers and artists. She is a class officer who, along with writing,...